Foreword by Yoshitomo Nara, Artist (English and Japanese)

And Yet, Here I Am

Apart from New York, I experienced all the cities contained in this book in realtime. Early 1980s Liverpool and London in England; Nuremberg and West Berlin in Germany; New York in America; and Tokyo, Japan. It was in 1980 when, not long after my 20th birthday, I “reallocated” the limited funds set aside for the following year’s tuition and worked my way south through Europe, by way of Pakistan.

A kid from a provincial city in the northern reaches of Japan, I had just moved to Tokyo and enrolled in art school. Surrounded for the first time by talented classmates from across Japan, my confidence was at an all-time low. I became a regular at the many live music venues and rock’n’ roll coffee shops blanketing Shinjuku and Shibuya. I still remember how junkies would begin to congregate around the South Exit of Shinjuku Station each afternoon, high on paint thinner and whatever else they could get their hands on. They looked like washed up hippies and stood out from the crowd who flocked to see all the punk and new wave bands. Whenever I saw them at shows, they seemed to try to dress and act the part, but their posturing couldn’t conceal an omnipresent cloud of sadness. Rather than feel the music, it looked like they had drifted into the clubs craving friendship. Either way, as if left behind by the wave of students and salarymen pouring into Shinjuku Station, there they were. As was I, on the periphery.

The first European city I ever set foot in was Paris. Nowadays, Japanese bookstores are full of conscientious guidebooks written for young travelers on a budget. But back then, I had to make do with Europe on $10 a Day, written by an American. True to the title, I ultimately did subsist on $10 a day. A prima facie art student, I had envisioned an itinerary full of art museums, but after only a few days in museum-ridden Paris, I’d soon had enough. Instead, I crashed in youth hostel after youth hostel, communing with fellow travelers and young locals who would come to hang out. Perhaps as a product of my youth, I found this mode of communication far more entertaining than cultured tourism. In a sense, I think this youthfulness was a hangover from my days spent in Shinjuku’s dimly-lit music hubs. So ingrained was this routine that I would roam the streets in search of such venues upon arrival in each big city, from Paris to Brussels to Amsterdam to divided Germany. At the time, West Berlin was like a landlocked country, isolated unto itself. I boarded an overnight train in West Germany. Passing through East Germany, we pulled into the last stop on the line at dawn: West Berlin’s Zoo Station. Exiting the gloomy station, I saw the ravished remains of a church across the street, left untouched since the war. The young people in Zoo Station differed from the delinquents in Shinjuku, as well as the punks and working-class skins I had encountered in London. They were the demographic who would later be depicted in the film Christiane F. Again different from the young people in Amsterdam who obtained spiritual liberation through drugs, they were shrouded in an over-whelming air of isolation and alienation. Though I was from the same generation, I could instinctively tell that I was nothing more than an interloper from a far and foreign country. At a cursory glance, I realized we wouldn’t be able to connect even over a discussion as simple as rock music or movies. They were engulfed in a whirlpool of nihilistic emptiness utterly unrelated to politics or religion. They showed none of the familiar traces of youth typically evinced in fashion or violence. Instead, they seemed to be in the process of being helplessly swallowed up in their own bottomless abyss.

I left Japan in the beginning of February 1980 and travelled through-out Europe practically penniless and in rags, returning home in early May. Having blown through my tuition, I had to withdraw from university. But I couldn’t have cared less. Of course, I felt that I had lost some important part of myself. Then again, I also felt that something intangible had been gained. I left Tokyo but was fortunately able to resume my studies the following year, this time at a private regional university.

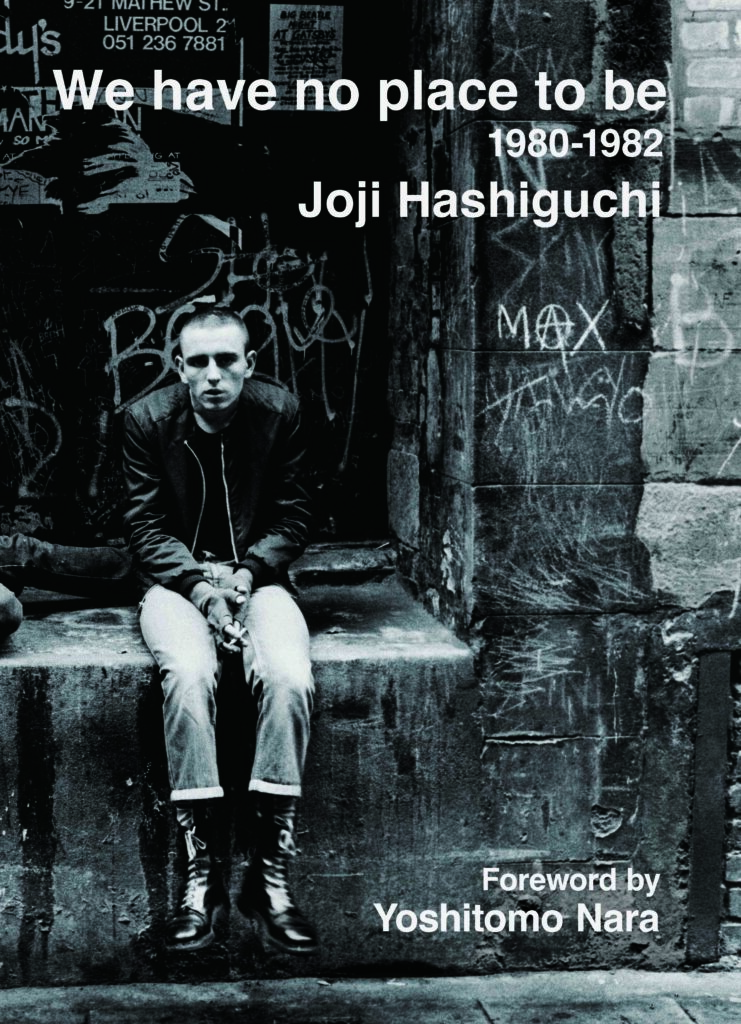

As ever, I wasn’t the best of students, but managed to make it through my studies without dropping out. Then, right when my European adventure was starting to become nothing more than a distant memory, I came across a certain photobook. I was immediately struck by the cover photograph and title: We Have No Place To Be. I flipped through the pages and made a beeline for the checkout counter. Leaving the bookstore, I sat down on the street for the first time in a long while. With each page, I slipped through time, transported back to London and Liverpool, Nuremberg and West Berlin. These photographs were the real deal. I found the nostalgic faces of all those who accepted me solely on the basis that we were of the same generation. I found the faces of youths branded with the badge of social outcast. I found the faces of young men and women who would ultimately be crushed under the weight of impregnable force. What I found transcended nostalgia. Within these pages, I discovered a feeling: what I wanted to say but could not articulate, what I hoped to paint but could not express. These photographs contained something that I could never hope to encounter in a school setting. Moreover, they contained something I thought only I knew.

The memories of my trip had been buried in the banalities of daily life, but they were revived by these black and white photographs, running through my mind accompanied by smell and sound. Like this photographer, I wanted to give voice to our generation. I resolved to devote my energies to elevating our tattered existence into something transcendent, something lasting and accepted.

The following year, I embarked on my second trip to Europe. This time, I was sure that art would provide my escape from this hopeless listlessness. For what followed, I thank Joji Hashiguchi and this wonderful book.

(Translation by Daniel Gonzalez)

序文:奈良美智、アーティスト

自分は、ここにいる

1980年代初頭、イギリスはリバプールとロンドン、ドイツはニュルンベルクと西ベルリン、アメリカはニューヨーク、そして日本の東京。この写真集に収められている都市は、ニューヨークを除いて、僕はどの場所も当時を知っている。20歳になったばかりの自分が、次の年に払うべき学費を使いこんで、パキスタン経由の南回りでヨーロッパに行ったのはちょうど1980年だった。北国の地方都市から上京して美大に入学したものの、日本中から集まった絵の上手い連中に敵わない、と自信を無くしていた頃だ。自分は新宿や渋谷でライブハウスやロック喫茶に出入りしていて、新宿南口あたりには昼間からシンナーや薬でラリっている奴らがいたのを覚えている。彼らはヒッピーくずれのような外見で、パンクやニューウエイブのライブに来る連中とは違っていた。ライブハウスで出会う奴らは、それなりに恰好つけていたが、みんな孤独感をまとっていて音楽に身をまかすことよりも誰か友だちを求めているようにも見えた。どちらにせよ、通勤通学で新宿駅を流れていく人の波から取り残されたように、彼らはそこにいたし、自分もその周辺にいたのだ。

そうそう、初めて降りたヨーロッパの都市はパリ。当時は若者向けの親切な日本語のガイドブックも無く『Europe on $10 a Day』というアメリカ人が書いた本を持って行った。まさしく一日10ドルの旅だった。美大生の端くれとして美術館を巡る旅になる予定だったが、早くも美術館だらけのパリでそれに飽きてしまった。そんな観光よりもユースホステルを泊まり歩き、そこで出会う旅人や訪れる町の若者たちとのコミュニケーションの方が楽しくなっていったのは若さのせいだったのだろう。その若さは新宿の薄暗いライブハウスから引きずってきたようなもので、大きな町に着くとそんな場所を探して路地を歩いていたのだと思う。そういうようにしてパリからブリュッセル、アムステルダムと移動していったのだが、まだ東と西に分かれていたドイツで、当時の西ベルリンは陸の孤島のような場所だった。西ドイツから夜行列車に乗り、東ドイツを通り抜けて終着駅である西ベルリンのZoo駅に着いたのは朝方だった。薄暗い駅を出ると、戦争で壊れたままの教会が通りの向こうに見えた。駅には新宿の不良少年たちやロンドンで見かけたパンクスや労働者階級のスキンズたちとも違った若者たちがいた。後に映画化された『クリスチーネ・F(原題 Christiane F.)』に出てくるような若者たちだった。彼らはドラッグで自由な精神世界を手に入れるアムステルダムの若者たちとも違って、圧倒的な孤独感や疎外感を身にまとっていた。そこでは僕はただの異国から来た同世代の旅人にしか過ぎなかった。ロックや映画の話題で盛り上がることすらも出来ないと、一目見てわかった。政治や宗教とは無縁の空虚がそこに渦巻いていたのだ。ファッションや暴力に表出される若さは無く、彼らはなす術もなく自らの奈落に吸い込まれていくように見えた。

1980年の2月上旬に日本を出てから、ほとんど無銭旅行のような旅をしてボロボロの恰好で帰国したのは5月の上旬だった。払うべき学費を使いこんでしまったことで、大学を辞めなければならなくなった。でも、そんなことなんてどうでもよかった。自分の中の何か大切なものを失ったような気もしていたが、何かを得たような気もしていた。東京の大学は辞めなければならなかったが、次の年の1981年、僕は運良く地方の公立大学に再入学することが出来た。

依然として優等生ではなかったが、ドロップアウトすることもなく学校に通っていた。そして、あのヨーロッパの旅が夢の中の出来事だったように遠い記憶になりかけていた頃、書店で一冊の本に出会ったのだ。『俺たち、どこにもいられない』そのタイトルと表紙の写真に惹きつけられた。パラパラとページをめくり、すぐにレジに直行した。書店を出て、久しぶりに路上に腰をおろした。ページをめくるたびに時間は逆行して、僕はロンドンやリバプール、ニュルンベルク、そして西ベルリンにいた。その写真は本物だった。同世代というだけで受け入れてくれた懐かしい奴らがそこにいた。社会的に不適格者の烙印を押された若者たちがいた。所詮は大きな力の下に潰されるのであろう彼らがいた。それは懐かしさではなく、自分が今、言いたくても言えない、あるいは描きたくても描けない気持ちの発見だった。学校の中にいては絶対に出会えないものが写っていたし、それは自分しかしらないとも思っていたものだった。日々の生活時間に埋もれていった旅の記憶が、その白黒写真から匂いや音を伴って脳内を駆け巡って戻ってきた。この写真家が撮るように、自分は自分たちの世代を絵にすればいいんだ、と思えた。ボロボロの気持ちでもって、それを定着させることに全力を注ぐのだと。

次の年、僕は2度目のヨーロッパの旅に出かけた。そして、絵を描くことで自分はこのどうしようもない状況から抜け出せるのだと確信していた。この写真集と橋口譲二さんに、改めて感謝します。

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Commentary by Mika Kobayashi, Photography Critic (English and Japanese)

Photography, Imagination, and the Other

Over the course of his long career, Joji Hashiguchi has remained an unfailing champion of the individual. Approaching his subjects with humanity, he has devoted his life to telling their stories to an indifferent society. Although most who stand before his camera can be nominally divided along abstract lines such as geographical region, social class, workplace, or school, Hashiguchi lends a sympathetic ear to each and every individual, documenting his subjects and their surrounding environs, the product of intimate engagement and discussion. At the heart of Hashiguchi’s work is a sobering sense of dedication to his subjects, reflected in an unwavering willingness to accept responsibility for the gravity of exposure before his lens. The moment a photographer picks up his camera, the power dynamic shifts, and the photographer can no longer be on equal footing with his subject. However, Hashiguchi has been careful not to impose his own value systems, instead maintaining a sublime sense of distance. With an open mind, he is accepting of the fact that even the observer becomes the observed, as the photographer is conversely exposed to the penetrating gaze of his subjects.

The present volume combines Hashiguchi’s acclaimed debut series Shisen (The Look)- recipient of the 18th Taiyo Prize in 1981- Oretachi Doko ni mo Irarenai: Areru Sekai no Judai (We Have No Place To Be), originally published by Soushisha in 1982, and many previously unpublished photos taken during the same time period. Available here in a new expanded edition for the first time in the West through Session Press, these works already reveal Hashiguchi’s nascent characteristic brand of engagement with his subjects. Encamped amidst the lingering, appraising eyes of young so-called furyo-“delinquents”-prowling the bustling night streets of Shinjuku, Harajuku, and Shibuya, Hashiguchi captures the posturing of the young with sensitivity, a lost tribe desperate for self-expression, repelled by a society that sings the praises of abundant riches and stability. Feeling stifled by the mounting pressures of home life and an increasingly oppressive education system, these youth sought out their own ephemeral space in the city. It’s on the streets where they learned to conduct themselves, and where Hashiguchi became a regular presence each weekend, submitting himself to their watchful gaze, continuing his work undaunted. In order to further study the conditions in cities, he left Japan in October 1981, embarking on an approximately three-month tour of Liverpool, London, Nuremberg, West Berlin, and New York. Over the course of this condensed itinerary, he came face to face with the harsh realities lurking underneath the surface of city life: drug addiction and self-destructive proclivities, racism and immigration issues, unemployment and poverty. Along each step of his travels, the local youth became a barometer for manifold social disarray erupting to the fore, the symptoms of complexly intertwined regional dynamics.

Although each country is undoubtedly home to its own unique social and historical context, these youths shared a common discontent and pent-up frustration that knew no outlet. Deviating from the traditional confines of societal norms, perhaps their violent behavior was an inheritance from their parents’ generation, the delayed manifestation of a wrinkle in the social fabric that emerged as an amplified distortion following the turbulent war years. Unable to choose their place of birth, these youths were conscripted to exist within their predestined location in time and history, all the while mouthing their cry, “We have no place to be.”

Hashiguchi walked those same streets, immersing himself in the culture to gain an intimate understanding of the voices and atmosphere of disenfranchised youth, closing in at point blank range to preserve their presence in photographs. Tape recorder in hand, he also interviewed his subjects, producing a body of reportage based on their raw testimony. Both mediums-image and language-depict distant worlds separated by vast oceans, populated with young people who proved to be not unlike ourselves. Moreover, Hashiguchi’s work is a vivid testament to the difficulty and unforgiving brutality of existence in one’s allotted place. When this book was first published in Japan, audiences were captivated by the predicament of these youths. A great many readers undoubtedly saw themselves in these young men and women living their lives in foreign lands. Indeed, Hashiguchi’s photographs have the power to jog the viewer’s faculties of imagination, inspiring recognition of the Self in the Other, and the Other in the Self.

Following the publication of We Have No Place To Be, Hashiguchi made repeated visits to Berlin to further his reportage on the city. Meanwhile, he embarked on an ambitious tandem project, traveling extensively throughout Japan from the latter half of the 1980s, meeting with the hoi polloi and documenting their stories in one-on-one portraits. The resulting series of Japanese subjects collected in photobooks such as Junana Sai no Chizu (Seventeen’s Map, 1988), Father (1990), and Couple (1992) eschew the pressing urgency of his street snapshots, instead utilizing an approach in which he takes a step back and puts some distance between his subjects, as if in studied repose. Even into the present day, Hashiguchi’s oeuvre serves as exploration and confirmation of existence, wherein everyone plays the hand they’ve been dealt.

Over 35 years have passed since these photographs were taken in the early 1980s. If the once-young people depicted in this volume are still alive, they will have already reached middle age. When we confront these photographs mindful of the passage of time, we find that they are more than simply a record of the nature of youth in a bygone era. Over a generation out, these images also contain tangential evidence of myriad deep-rooted problems-racism and the immigration debate to name two-that remain just as relevant and pernicious in the present day.

Compared to the 1980s, at first glance, it may seem that we live in an era of relative quietude. However, not far beneath this veneer of deceptively peaceful existence pulses the same primal cry, “We have no place to be.” This sentiment, a plea for belonging, remains a visceral part of our everyday lives, often experienced though not necessarily articulated. The act of viewing photography thus constitutes one means of confronting the past, providing perspective that elucidates the present in stark relief. For the generation who lived this era, these photographs provide an opportunity for reflection on the past through the lens of age. Similarly, these photographs will enable a younger generation to understand the experiences of their forebears. In this sense, Hashiguchi’s work is a timely cross-generational addition to the modern milieu. Speaking to a higher calling, perhaps his photographs will allow us all to ford new channels of imagination, connecting past to present.

(Translation by Daniel Gonzalez)

解説:小林美香、写真研究者

他者への想像力の回路を拓く写真

橋口譲二は、一貫して「個」としての人に向き合い、その存在を広く社会に伝えることに身を賭してきた。カメラの前に立つ被写体が、それぞれに地域や社会階層、職場や学校のような集合体に帰属することを前提としながらも、一人一人の声に耳を傾けて対話を重ね、その姿を周囲の環境と共に写し取る。橋口の写真の根底には、一貫して被写体がレンズの前に晒されることの重みを引き受ける覚悟、生真面目な姿勢がある。カメラを手にした瞬間、写真家と被写体が対等な立場にはなり得ないが、彼は自分の価値観を他者に押しつけるのではなく、他者との距離を測りながら虚心に見つめ、撮影する側もまた視線に晒されるという事実を受け入れてきた。

橋口のデビュー作として注目を集めたシリーズ『視線』(1981年に第18回太陽賞を受賞)と『俺たち、どこにもいられない 荒れる世界の十代』(草思社、1982年) そして、この度新たに発表された東京の作品を元に編まれた本作では、橋口の被写体に対峙する姿勢の原点が表されている。橋口は新宿や原宿、渋谷のような繁華街にたむろする、いわゆる「不良」と呼ばれる若者たちが放つ視線の中に、虚勢を張りながら精一杯の意思表示をする態度を感じとる。豊かさと安定を謳う社会の中で抑圧力を強める管理的な学校教育や家庭に息苦しさを感じ、そこからはじきだされた若者たちは、都市の路上に束の間の居場所を見出し、お互いに視線を送りながら路上での振る舞い方を身につける。週末毎に彼らのいる繁華街に通い視線に身を晒して撮影に取り組んだ橋口は、都市のありようをさらに探究すべく、1981年10月末から約3カ月をかけリバプール、ロンドン、ニュルンベルク、西ベルリン、ニューヨークと五つの都市を巡った。凝縮された旅程の中で、豊かな社会に潜む薬物依存などの自傷行為の問題や、人種差別や移民問題、失業、貧困など、都市、地域ごとにさまざまな要因が絡み合って噴出する社会問題の実情を、出会った若者たちの中に見出していった。

それぞれの国で社会的背景や来歴はことなるものの、若者たちが抱えるやり場のない不満や鬱憤は共通している。社会的な規範を逸脱し、暴力的な彼らの行動は、第二次世界大戦前後の激動期を潜り抜けた彼らの親世代から引き継がれ、しわ寄せてきた歪み(ひずみ)が浮き上がって姿を現したものなのかもしれない。誰もが生まれる場所を選べず、その場所の歴史の中に生きている、「俺たち、どこにもいられない」と叫びながら。橋口は、路上で若者たちの発する声や匂いを皮膚で感じ取り、その姿に肉薄して写真に捉えるとともに、テープレコーダーで録音した彼らの肉声を元にルポルタージュを綴った。橋口の写真と言葉は、日本から海を隔てた遠い国の都市でも、若者たちが同じ地平線上にいること、与えられた場所で生きることの困難さ、残酷さを鮮やかに描き出している。この本が日本で刊行された当時、多くの読者は写真と言葉によって捉えられた若者たちの置かれている状況に心を奪われ、異国に生きる彼らの姿の中に自分たち自身を見出したのではないだろうか。橋口の写真は、他社の中に自分がいて、自分の中に他者がいるという想像力を見る者の中に切り拓く力を具えている。

『俺たち、どこにもいられない』を刊行した後、橋口はベルリンへの渡航と取材を重ね、併行して1980年代後半からは日本各地で市井の人々一人一人に対面して撮影する息の長いプロジェクトに取り組んでゆく。『十七歳の地図』(文藝春秋、1988)や、『Father』(文藝春秋、1990)、『Couple』(文藝春秋、1992)のような写真集としてまとめられた日本人のシリーズは、肉薄した路上のスナップとは異なり、佇む人たちを距離を置いて捉える撮影方法が用いられているが、誰しも与えられた場所で生きていることを確かめる姿勢は、現在にいたるまで揺らいでいない。

1980年代初頭から35年以上の時間が経過した現在、本作の写真に捉えられた若者たちは、存命であれば50代前後の中年である。一世代以上の時間的な隔たりを念頭に置きながらこれらの写真に対峙すると、過ぎ去った時代の若者たちの様相を捉えた記録としてだけではなく、人種差別や移民問題など現在にいたるまで根深く残るさまざまな問題の一端が写し取られていることが浮かび上がってくる。一見豊かさに溢れ、1980年代当時に比べれば平穏に見える日常の皮膜のすぐ下に潜む「どこにもいられない」と心の中で叫ぶ存在を、私たちは日常生活の中で肌で感じ取っている。写真を見ることは、過去に対峙し、そこから現時点を照射する視点を得る一つの術となる。写真を通して、当時を知り年齢を重ねた世代が過去を振り返ることも、若い世代が親世代の経験を知ることもできる。橋口の写真は現時点にあって、さまざまな世代の人にとって、過去と今をつなぐ想像力の回路を切り拓く役割を担うものになるのではないだろうか。

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

レビュー:ロバート・ダン、ライター・写真家・教師

FAR MORE THAN”PRETTY VACANT”,WE HAVE NO PLACE TO BE BY JOJI HASHIGUCHI

パンクロックの時代を撮った写真集は多数ある。あの激しい時代を撮った作品は、鮮やかな写真で埋め尽くされている。ラモーンズやピストルズのコンサート会場にひしめくスキンヘッドの男たち、左右に跳躍するタトゥーだらけの肉体、飛び交う拳、むき出しの歯、吹き出す血液・・・・・力強い絵だが、こうした作品の多くはクラブでのライブやスターたち、舞台から見たCBGB、ダウンタウンのストッキングの破れた女性たちがたばこを吸ったり酒を飲んだりしているようす(テーブルの上にこぼれた化粧の粉のカットが華を添える)、モヒカンの若者がうろついているようす。それはいかにも80年代な・・・・・とうの昔に過ぎ去った時代の作品になっている。

彼らに賛辞を送ろう。80年代初頭の若者は阻害と冷笑が絶妙に混ざり合った独特な世代だった。60年代後半のように、LSDで意識の拡張をめざしたヒッピーたちではない。自然志向からアースシューをはいた70年代の若者でも、同時代に映画「ウォール街」のゴードン・ゲッコーをまねて蝶ネクタイを締めたヤッピーたちでもない。よもや現代の、インスタグラムやティックトックで再生数を稼ぐために髪を色とりどりに染めることに夢中になっている若者たちではない。

当時の若者は真にサブカルチャーの一部だった。サブカルチャーという概念は今や失われたか、塗り替えられている(CBGBsが今、デザイナーのジヨン・ヴァルヴェイトスの店に変わっているのは周知の事実だ)。本当のサブカルチャーとは、普通の、伝統的な世界の外にある、明らかに異なる小さな文化圏だ。サブカルチャーの住人は自分たちの縄張りの中だけをうろつき、自分たちのドレスコードを持ち、支配的な文化からは黙殺されるか、恐れられている(今サブカルチャーの住人は毎晩のように夜遊びせず、ヘッド・バンキングをしない。彼らはソファーで丸くなり、ネットの片隅に集まっている)。

サッチャー-レーガン時代の若者は、真剣に不満を抱いていた。ピストルズが「プレティ・ヴェイカント」(かなり空っぽ)を世に出したとき、そのタイトルは皮肉だったのだと思う。かつては、サブカルチャーの一部であるということは体もこころもそっくりそのまま入れ込む、ということだった(JPモルガン証券にスキンヘッドの社員はいなかった)。完全に入れ込む。家はない。行く場所なんてない。橋口譲二の新作『俺たち、どこにもいられない』がいうように、サッチャー-レーガンの時代には、彼らの居場所はなかった。就ける職も、受け入れる世界もなかった、彼らを支えたのは空っぽのニヒリズムだけだ。

そしてそれはおそらくたいした慰めにもならなかった。橋口氏の作品を開くと、私たちは彼らと出会える。どこにもいられない彼ら、1982年初版の本を直訳すれば『俺たち、どこにもいられない 荒れる世界の十代』。彼らはセレブでも、バンドでもなく、スターだとは口が裂けても認めないスターでもない。このざらざらした世界の中で混乱し、絶望し、誇りを持って生きている人たちだ。

だからこそ、この写真集はより豊かだ。

そして美しい。8・25インチ×11・25インチの大判な本で、写真はどれもコントラストの激しい白黒写真だ(出版社はセッション・プレス。そういえばお分かりだろう)。1980年から82年にかけて、橋口氏は世界を旅した。まずはリバプールへ(彼はビートルズのファンだった)、それからロンドン、ニュルンベルク、西ベルリン、そして東京へ。怒れる若者を追いかける、まさに長い修行の旅(ドイツ語で、修行を終えた職人が旅する伝統を指すWanderjahre)だった。橋口氏はサブカルチャーの巣窟を、いつも暖かいまなざしと共感を持って探検した。

橋口氏はただ単に、決定的瞬間にシャッターが切れるだけの人ではない。彼は本物の写真家だ。この作品には、時代の記録という以上の意味を持っている。もちろん、国から国へと移動していくスタイルは、エド・ヴァン・デル・エルスケンの『スウィート・ライフ』を彷彿とさせる。冗談半分でこの作品をエルスケンにちなんで「サワー・ライフ」と名付けたら、多くの写真はマッチすると思う。しかしすべてではない。

屈強なスキンヘッドが大勢いる。ベルリンでは薬物中毒が少なくとも2、3人写っている。しかし一方で、ファストフード店「ウィンピーズ」の制服を着てはつらつと笑う若い女性2人のカットもある・・・・・ウィンピーズで働いていて、どうやって幸せでいられるというのだ?でも彼女たちは幸福なのだ。

ヴァン・デル・エルスケンのように、橋口氏の本は広い世界を股にかけている。白黒のコントラストの強い作品も似ている。森山大道的な世界観もある。しかし橋口氏の意図は、7割程度は「いい写真」を撮ることではなく、彼が愛してやまないこの若者の世界をとらえることにあるようだ。

私の計算が正しければ、橋口氏はこの撮影旅行のとき、30代前半だったはず。当然、彼は被写体の観察者だったのか、あるいは当事者だったのか、という疑問が浮かび上がる。おそらく両方だったのだと思う。だからこそこの本は力強い絵を集めた写真集であると同時に、ドキュメンタリーなのだ。

すべての章は、それぞれの街で彼が出会った人物の台詞から始まる。リバプールの若者は言う。「金もない。仕事もない。俺の人生ないも同じさ」。ニュルンベルクの若者は「何もすることがなくて、退屈だった。あの頃、私のまわりには、ヘロインしかなかったの」。東京の若者は切迫度はかなり低い。「娯楽がしたいよ。一般ピープルはラクでいいねぇ」。そしてそれぞれのセリフの温度が異なるように、被写体や写真のトーンも異なる。私はN.Y.の写真に特に感心した。どうやら橋口氏は若いラティーノや、黒人の若者とつるんでいたようで、スコセッシの「ミーン・ストリーツ」の世界観から少しイタリア色を抜いたような感じになっている。この章の作品は被写体が写真家をまっすぐ見つめている、率直な写真が多い。他の章で橋口氏は路上をゆく多様な人々を撮っている。街を徘徊する若者の集団や、道行く普通の人々。リバプールの屋上から街を見つめる6人の少年をとらえた1枚はとくに美しい。それでも、私は彼が対象をしぼっているとき、写真家としての真価が現れているように思う。N.Y.章では画面いっぱいに肉体が映し出されていて、力強い。冒頭のリバプールのセクションはあまりとげとげしさを感じない。ロンドンの方がタフな印象を受けるし、薬物を撮ったベルリンはもっとも力強い。写真家が東京に帰ると、作品は強いのだが、そこでは子どもが子どもらしく過ごしている。仲間と集まったり、かわいらしいバイクを乗り回したり。イギリス、ドイツ、アメリカの写真よりも、笑顔の写真が多い。

『俺たち、どこにもいられない』が彷彿とさせる写真家がもう一人いる。アンデルス・ペーターセンだ。ペーターセンの写真はもっと緊迫していて、悲痛で、多くの場合目を背けたくなる。代表作『Cafe Lehmitz』では無秩序な生命力を活写し、ある特定の場所の深い記録を残した。橋口氏はもっと手広く、ペーターセンや森山大道のような芸術家ではないのかもしれないが、しかしやはり『俺たち、どこにもいられない』のような作品は他にない。

深く見れば見るほど、この写真集はパンクの本ではない。怒れる若者のものだけでもない、白黒写真の集成といえるのかもしれない(リバプールの章で、たき火の閃光だけが写った1枚と、ゴールデンスクエアレストランのメニューが写された1枚が含まれているのが好きだ。ああ、イングランド!私が貧乏な24歳として初めて訪れたときにそうしたように、橋口氏もゴールデンスクエアで春巻きやソーセージ、カレーとチップス、チップスと豆、そしてあのイギリスの素晴らしい、つぶした豆のスープをたった14ペンスで食べたのだろう!)。

その意味で、『俺たち、どこにもいられない』は日本の写真集の古典の一つに位置づけるのが適当だろう。どれだけ眺めても飽き足らず、見返すたびに素晴らしい写真がある。中平卓馬らが発刊した『PROVOKE』に親和性の高い作品もある。N.Y.の章のカットの数枚は、東松照明のいくつかの傑作を思わせる(若い男性が猛烈な勢いでサンドバッグを殴っている写真と、白い服を着た学生が完璧にぼけた背景の前に立っている写真だ。ああ、新宿!)。『俺たち、どこにもいられない』は東松や森山らの詩的領域にはいない(誰がそこにいるだろう?)。だが橋口氏の写真の作品はより生き生きとした歴史的な記録であり、再評価に値する写真家だ。強くおすすめする。

(翻訳:榎本瑞希)

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Reviews

–British Journal of Photography by Marigold Warner (3.9.2020)

–PHOTOBOOKSTORE MAGAZINE by Robert Dunn (3.18.2020)

–photo-eye by John Sypal (4.20.2020)

–JOURNAL・BRIAN ROSE (4.20.2020)

–alfalfa studio by Rutwik Ingale (9.3.2020)