Individual-Japan and Japanese : 日本と日本人

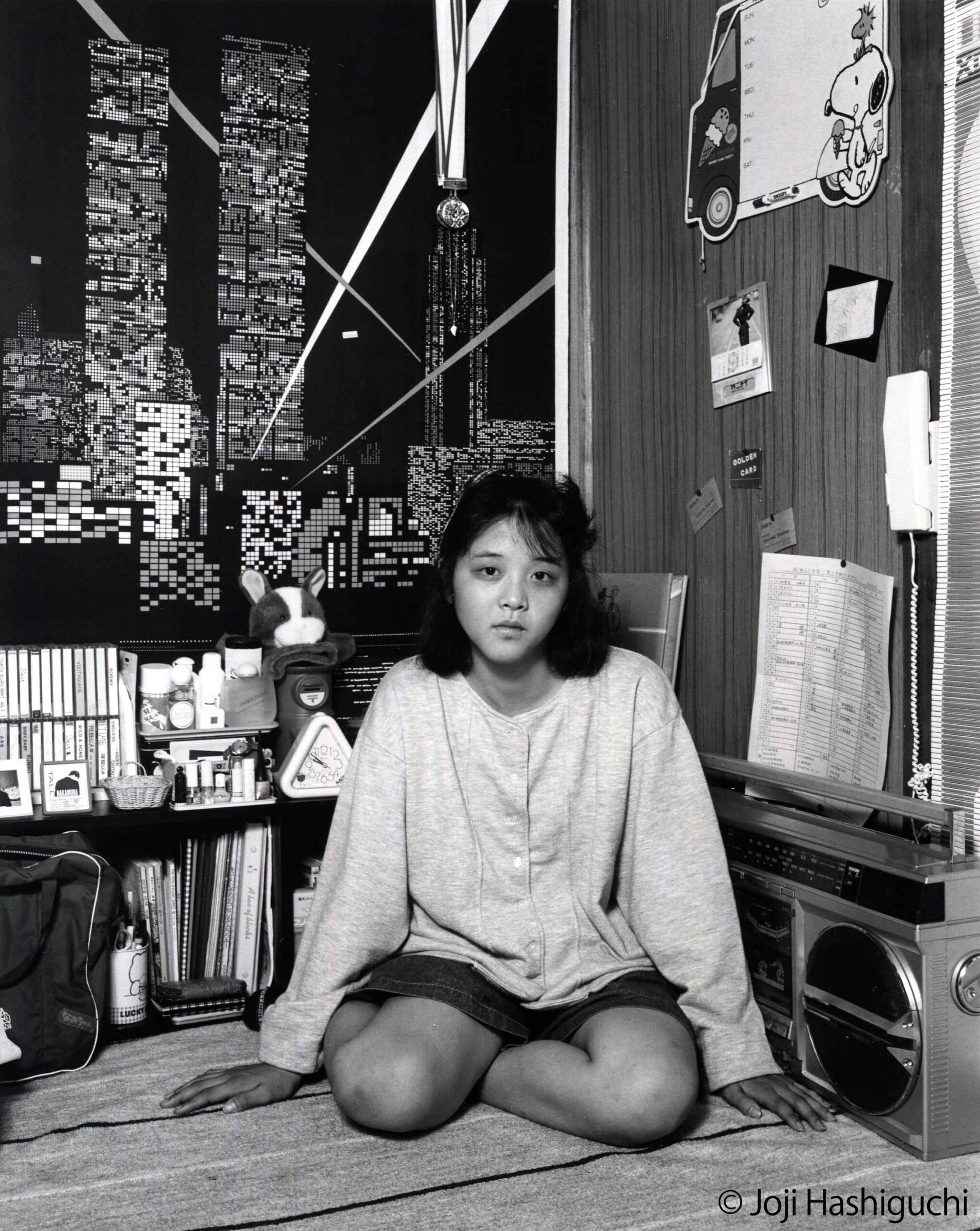

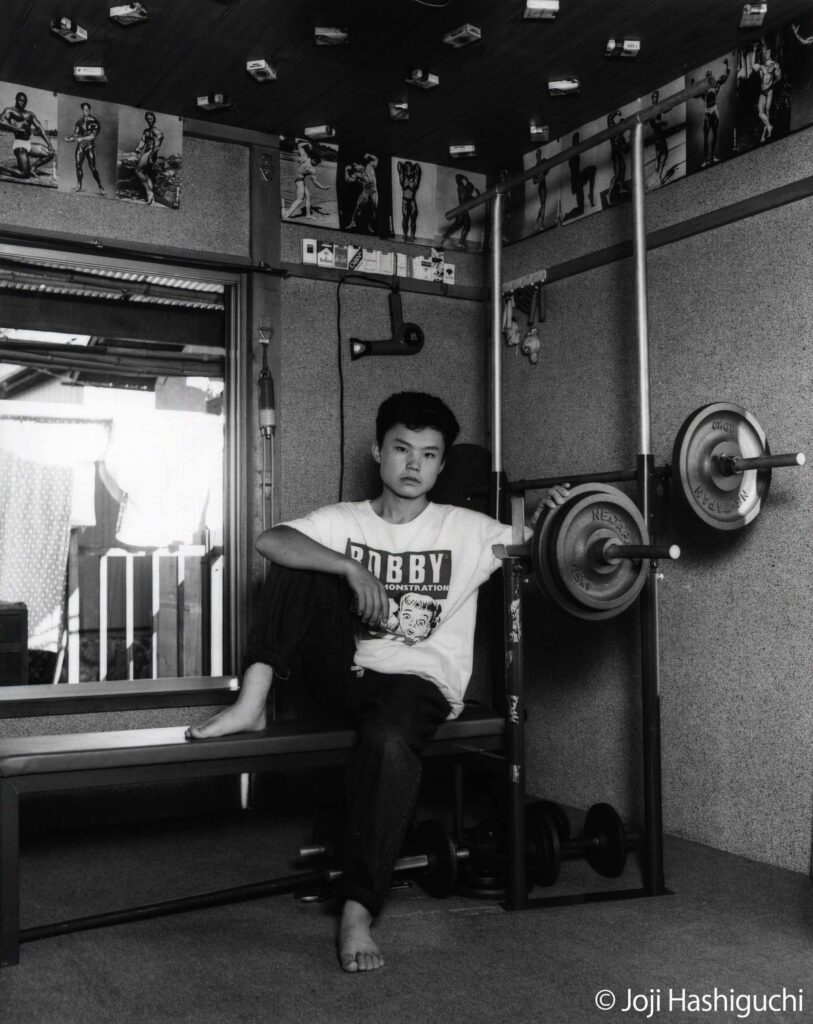

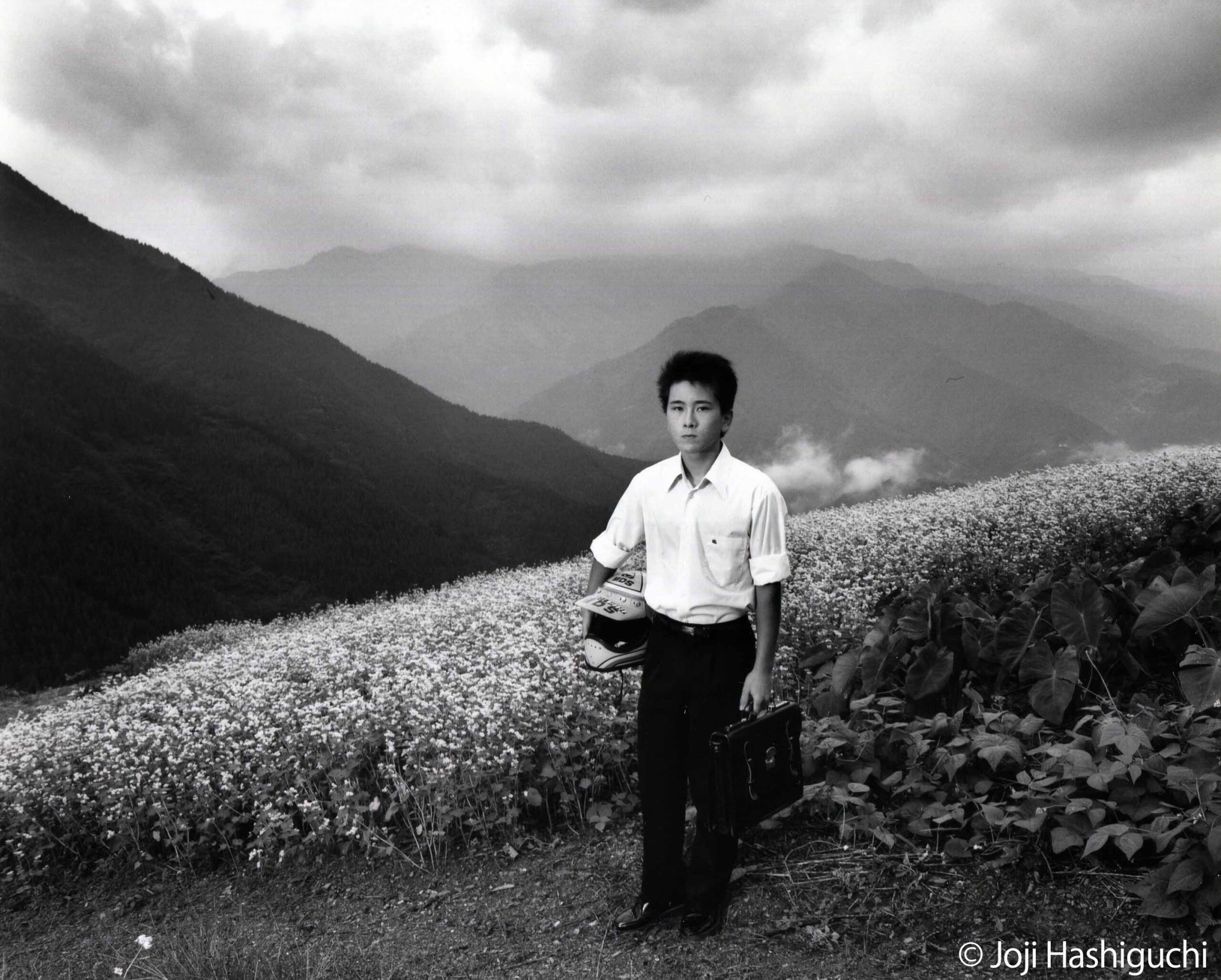

“Seventeen’s Map” 1988 (Bungeishunju) : 『17歳の地図』1988年 (文藝春秋)

“Seventeen” 2007 (Sangyohenshu-center ; New Edition) : 『17歳』2007年 (産業編集センター;新装版)

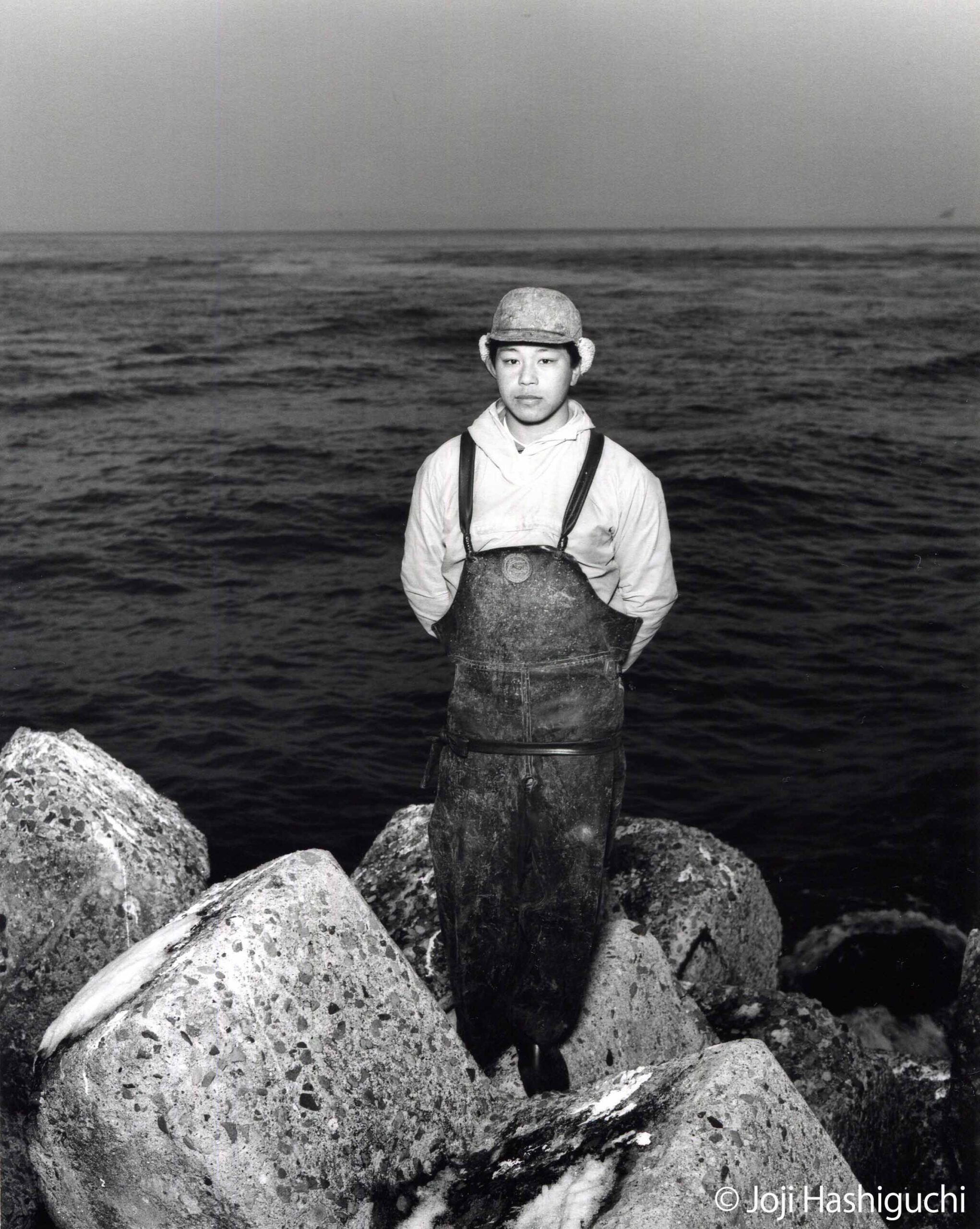

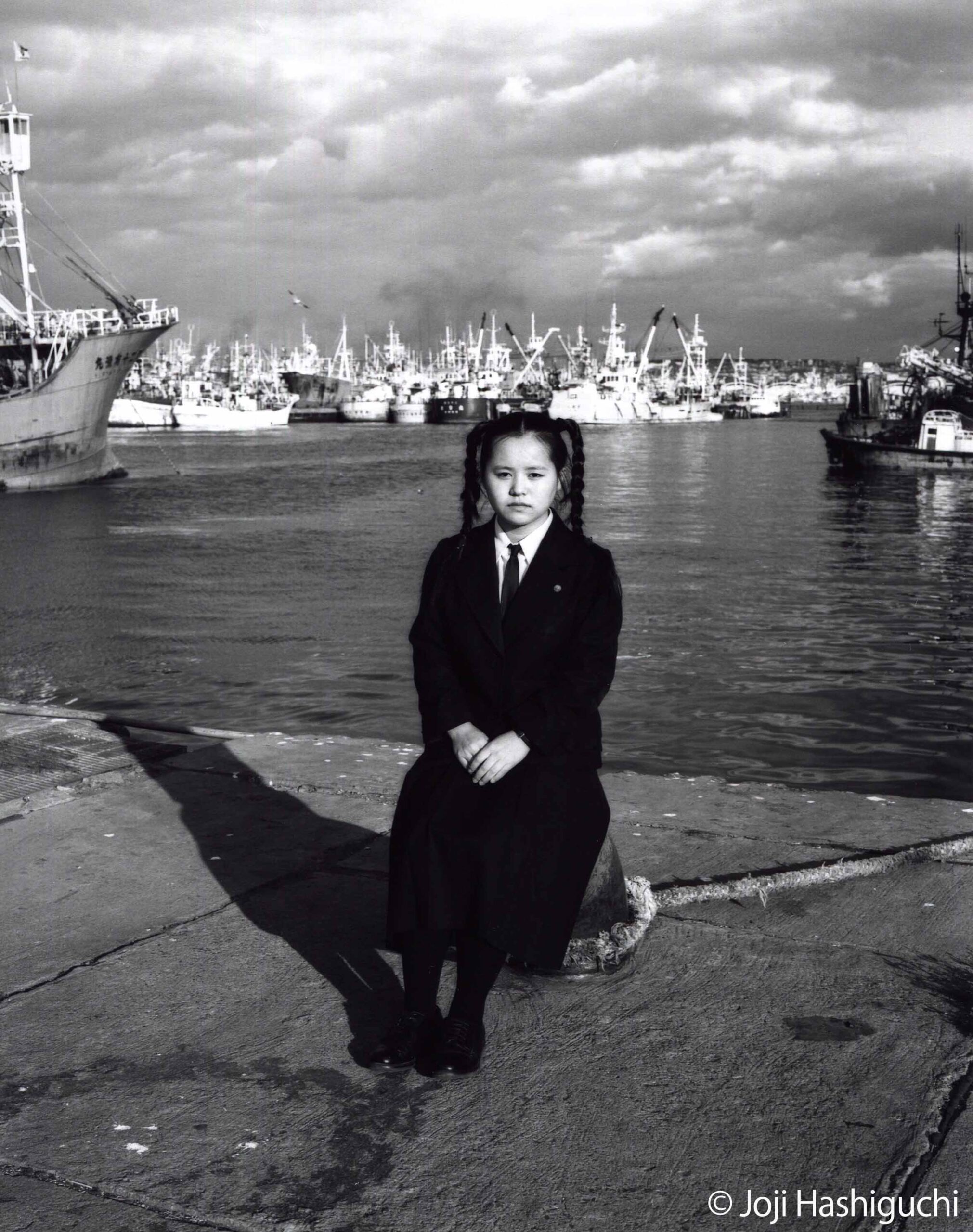

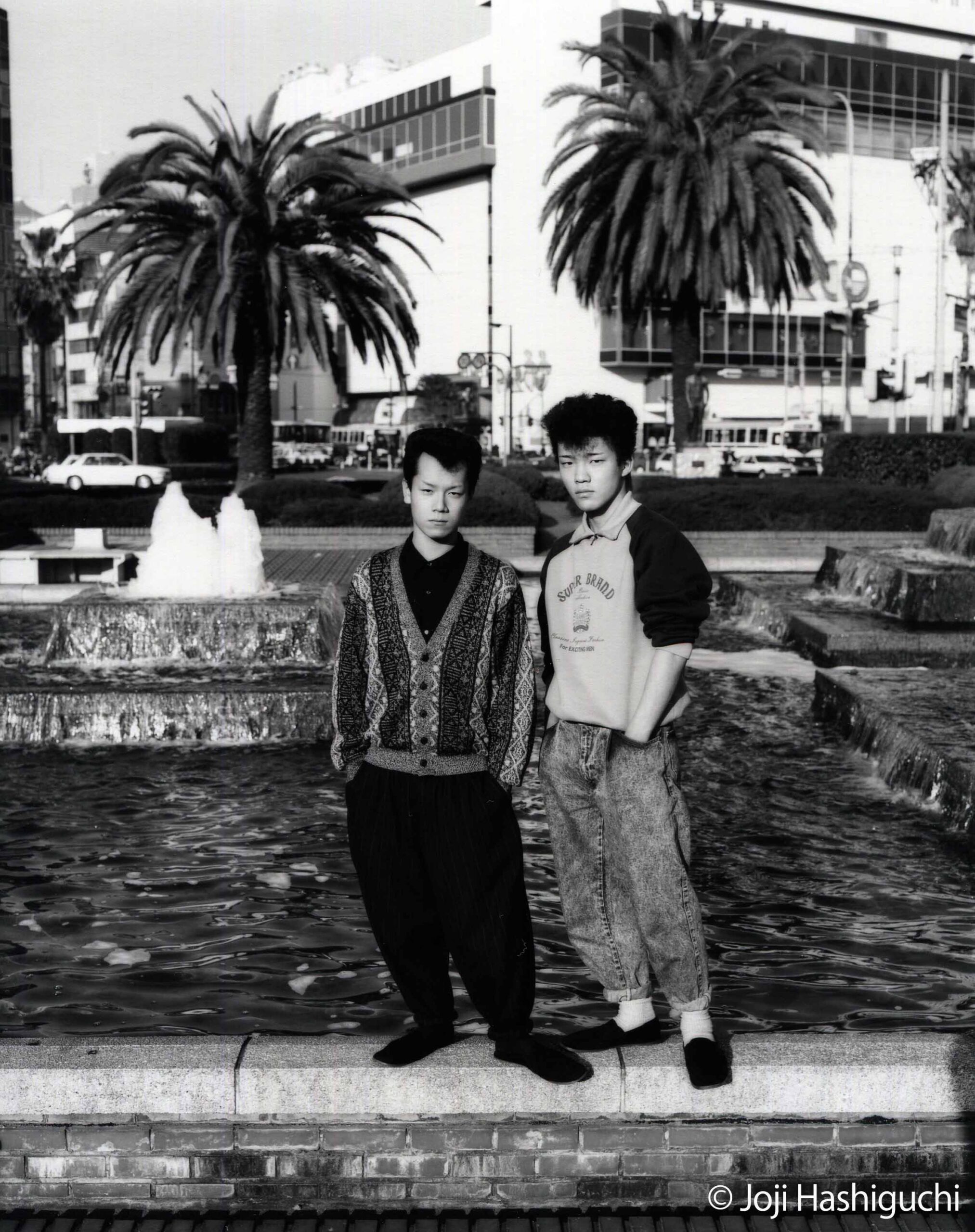

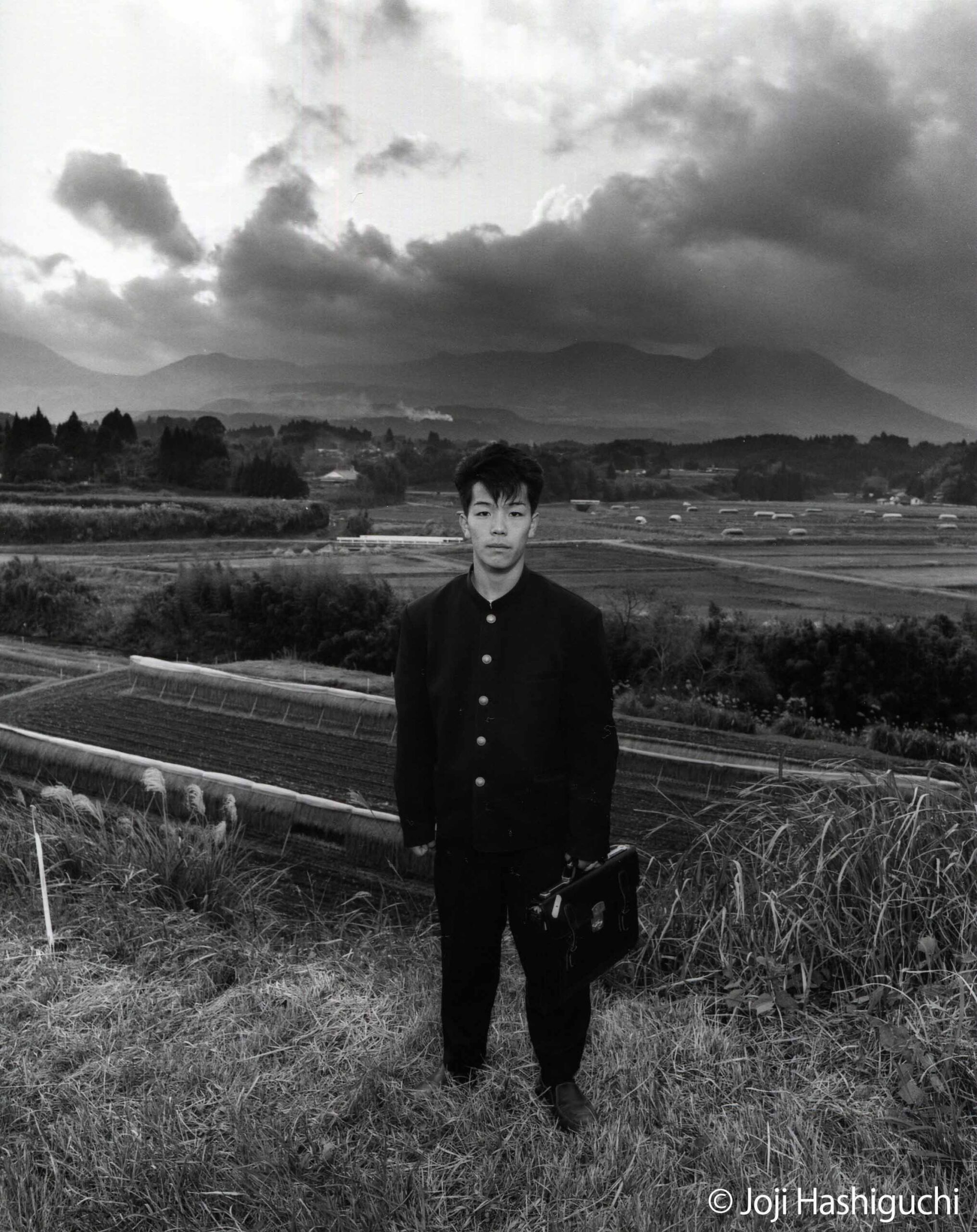

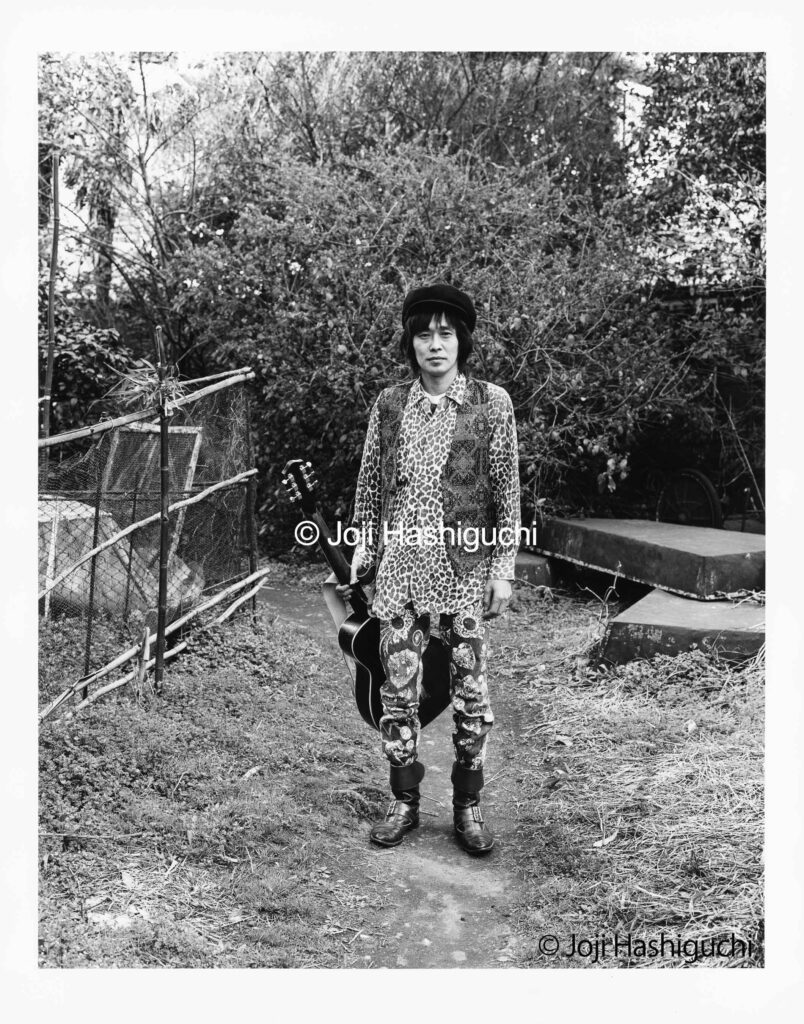

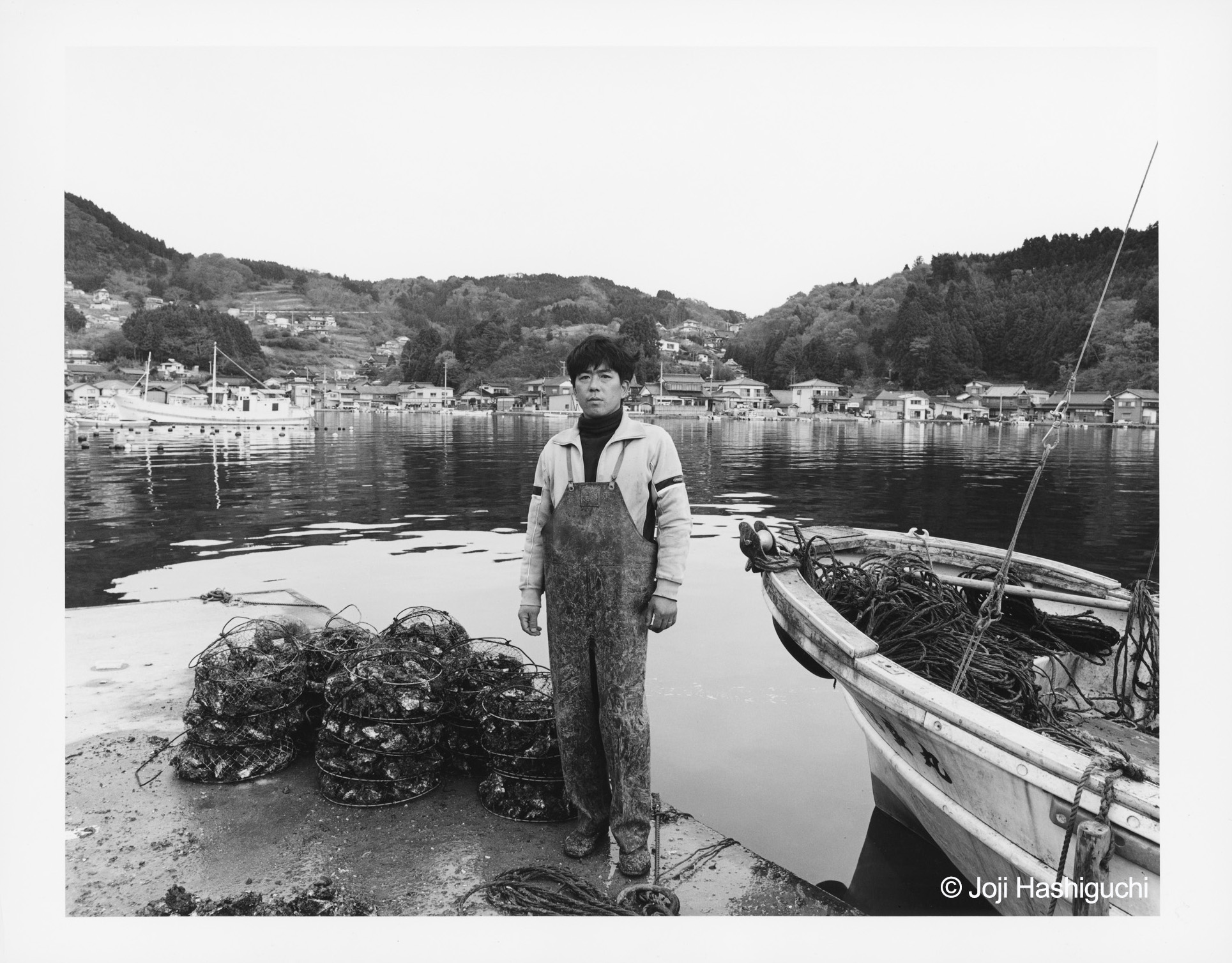

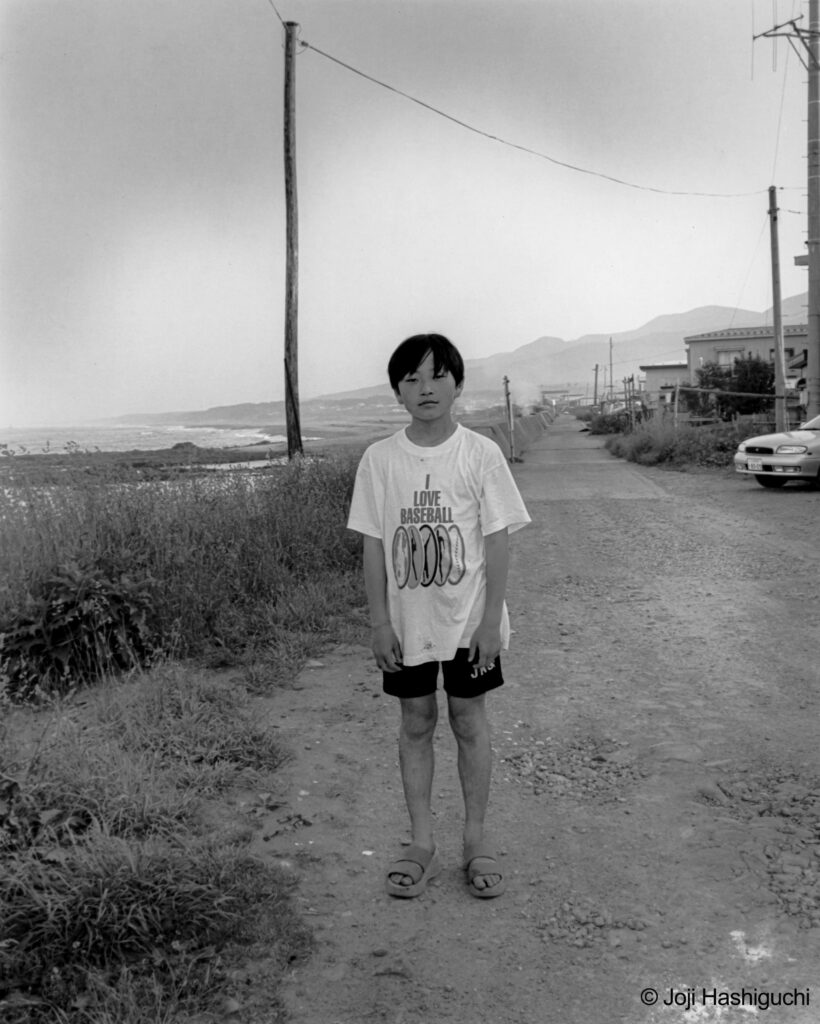

From March 1987 to January 1988, I travelled almost the whole of Japan, up north to the Rebun Island in Hokkaido, and down south to the Yonakuni Island in Okinawa. This is a collection of the pictures of the 17-year olds at the moment when I met them and pressed the shutter of my camera, I did not care who my models were. In return for letting me photograph them, I decided not to pick and choose, but to put them all into this book.

I wanted to see with my own eyes, and check in my own way, the Japan today where everything in society seemed about to flow forth in one direction. I wondered whether there wasn’t a common factor with which to get a cross section of Japan. The answer was, again, teenagers. Having worked with teenagers, I had the feeling that 17 was an important time in determining one’s future life. By coming face-to-face with 17-year olds, by representing them in their own surroundings through photography, I wondered if I couldn’t express the differences among the 17-year olds of Japan, and thereby get a picture of Japan today. This was how this work got started.

1987年3月から1988年1月にかけて、北は北海道の礼文島、南は沖縄の与那国島まで僕はほぼ日本全国を旅した。ここに集めたのはその旅の中で出会った17歳たちの姿である。その土地で出会い、シャッターを押した時点で17歳でありさえすれば誰でもよかった。その代わり、写真を撮らせてもらった以上は一切セレクトは行わず、全員に写真集に登場してもらった。

社会が一つの方向へ流れだしていこうとしている現在の日本を自分の眼で、そして自分なりの方法で確かめてみたかった。何か一つの共通項で日本を水平に切り取ることはできないだろうかと考えた時、やはり僕にとって一番気になる存在は10代だった。10代と関わる仕事の中で、17歳というのはこれからの生き方を決めていく上での重要な時期なのだと僕は感じていた。17歳と向き合って顔を見合い、彼らの環境をも写し出すという写真表現の作業を通じて日本の17歳のいろんな違いを浮き彫りにし、同時にいまの日本が見えてくるような試みはできないだろうかーそんな思いから今回の仕事は出発した。

Shooting date: Mar.1987- Jan.1988, 102 people in total

ー写真集『17歳の地図』と、シンガーソングライターの尾崎豊さんのアルバムタイトル「17歳の地図」との経緯についてー

結論を先に書くと、尾崎豊さんのアルバムタイトルを使わせてもらいました。写真集タイトルとして使用するにあたり、僕は尾崎さんと彼の事務所に手紙を書きました。この時、尾崎さんに宛てた手紙は彼のファンクラブの会報に掲載されました(これは尾崎さんと彼の事務所の、僕と写真集に対しての配慮だと想像しました。ありがたかったです)。

尾崎さんのアルバムタイトルを写真集タイトルとして使わせてもらった理由についてですが、僕が自分の意志で撮影をスタートさせた時のタイトルは「17歳」でした。撮らせてもらった人の名前、住所、家族構成に「今朝の朝食」などの共通質問を記すインタビューシートも「17歳」でした。そして撮影が終わり写真集としてまとめるにあたり当時、縁のあった文藝春秋を訪ねました。写真集出版については快諾してもらえました。ありがたかったです。ただ、「17歳」のタイトルは使えない、その理由はコラムニストのボブ・グリーンさんの本が同じ版元で準備されていたからです。

タイトルについてはいろいろ悩みましたが、仕上がった写真世界と尾崎豊さんが歌う世界と重なるものがあると思い、面識はありませんでしたが彼に手紙を書くことにしました。写真集発表後も尾崎豊さんとの個人的な行き来は生まれませんでしたが、尾崎さんの復活コンサートは彼のご両親と一緒に見せてもらいました(これも彼の事務所の配慮だと想像します)。

尾崎豊さんが不慮の死を遂げた後、彼の死をスキャンダルで終わらせてはいけないと思い、岩波書店の雑誌『世界』に追悼文を書かせてもらいました。

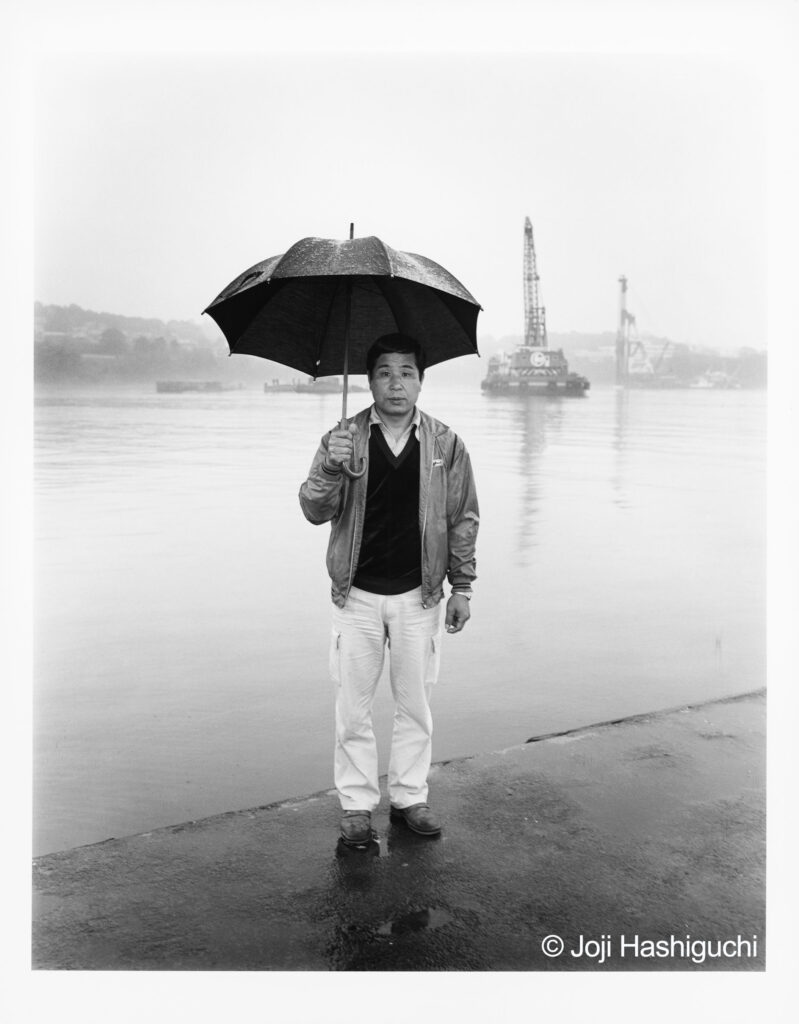

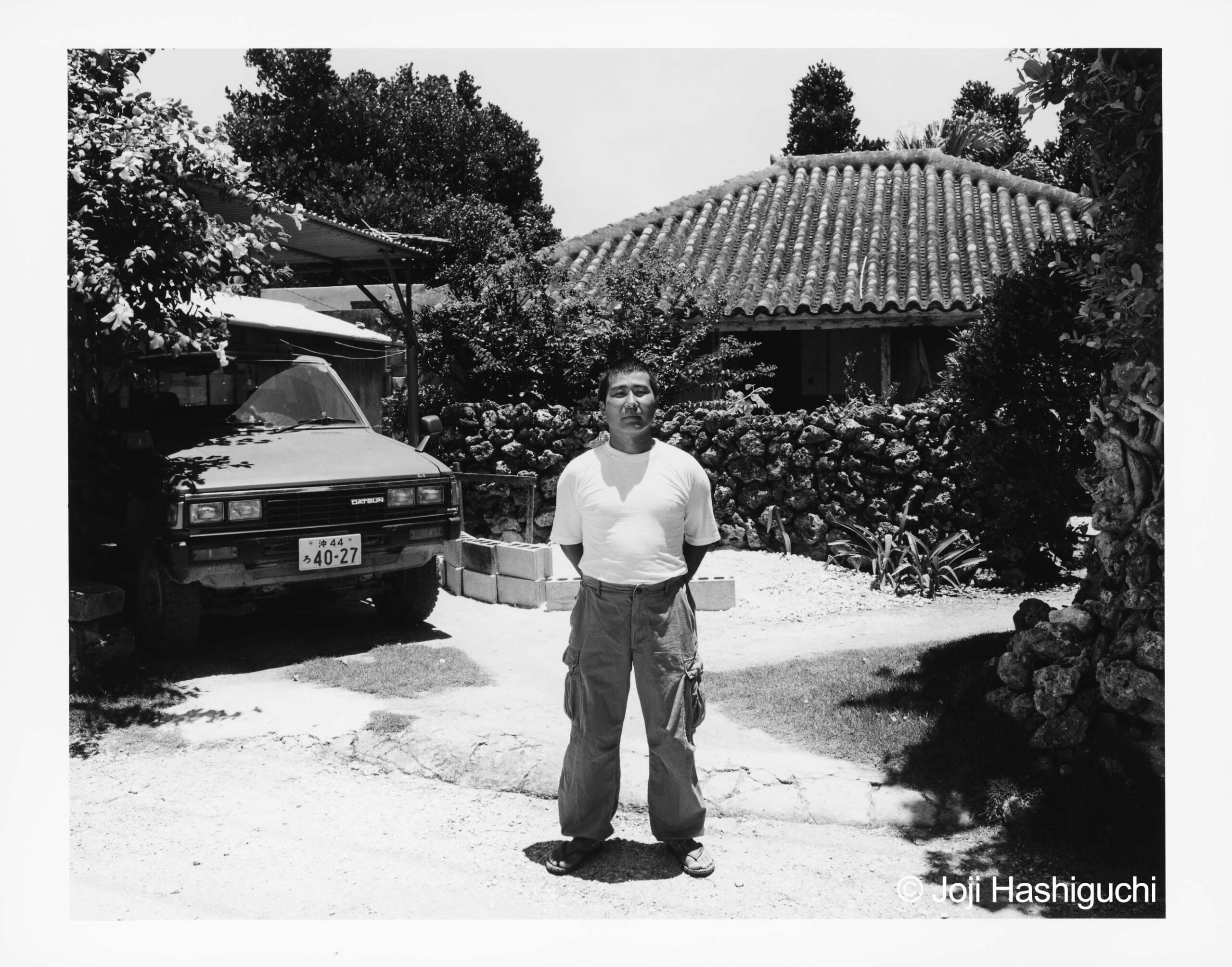

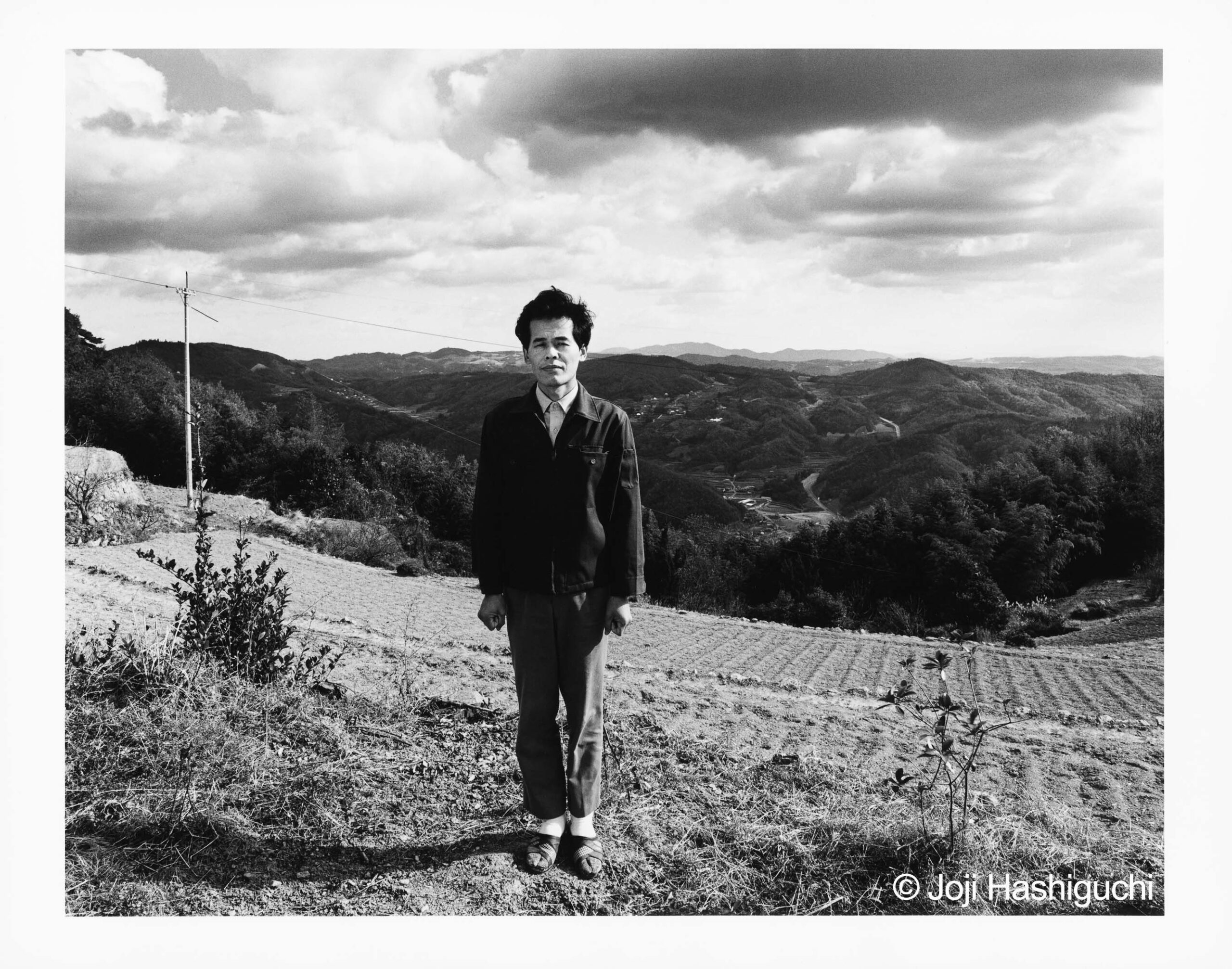

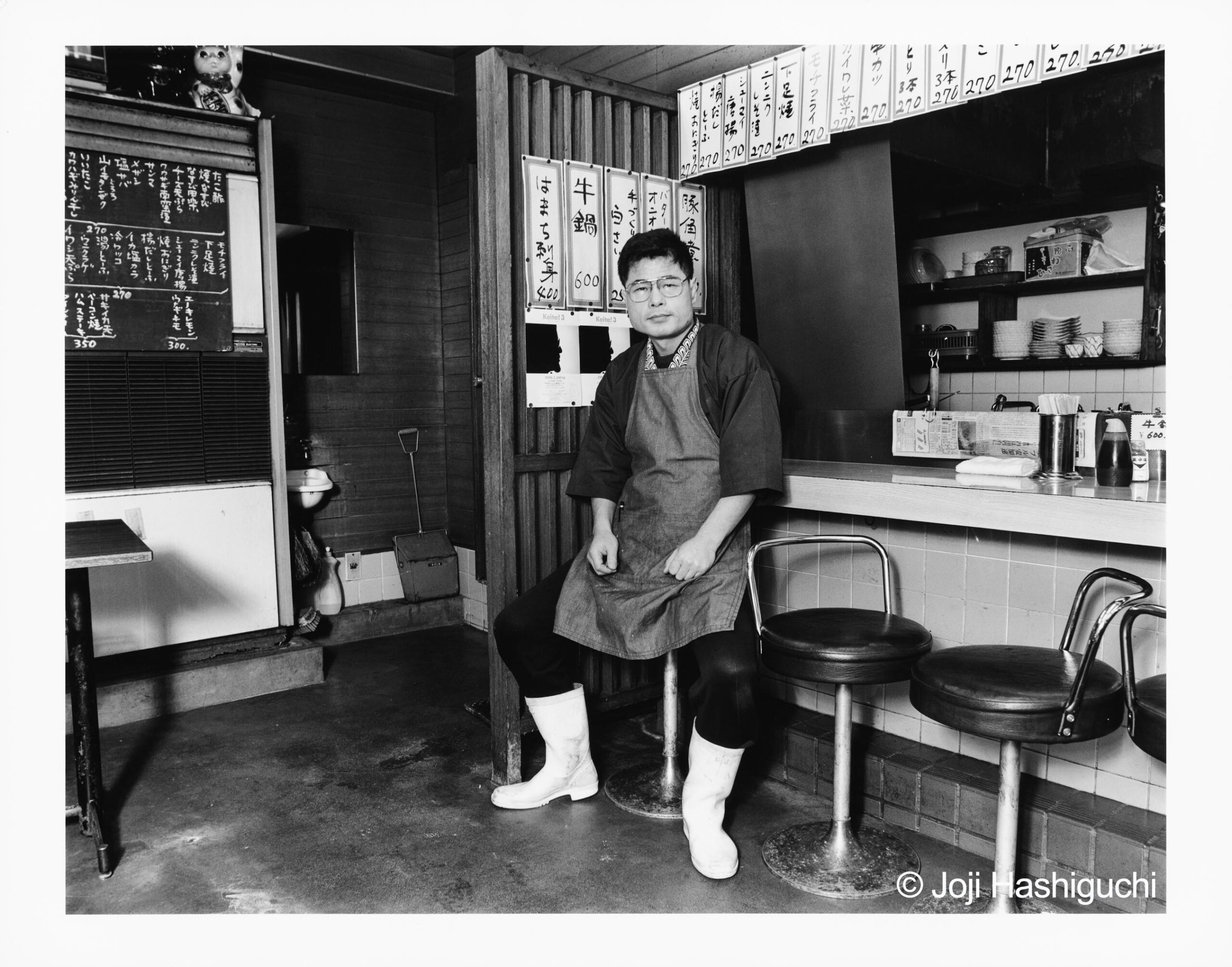

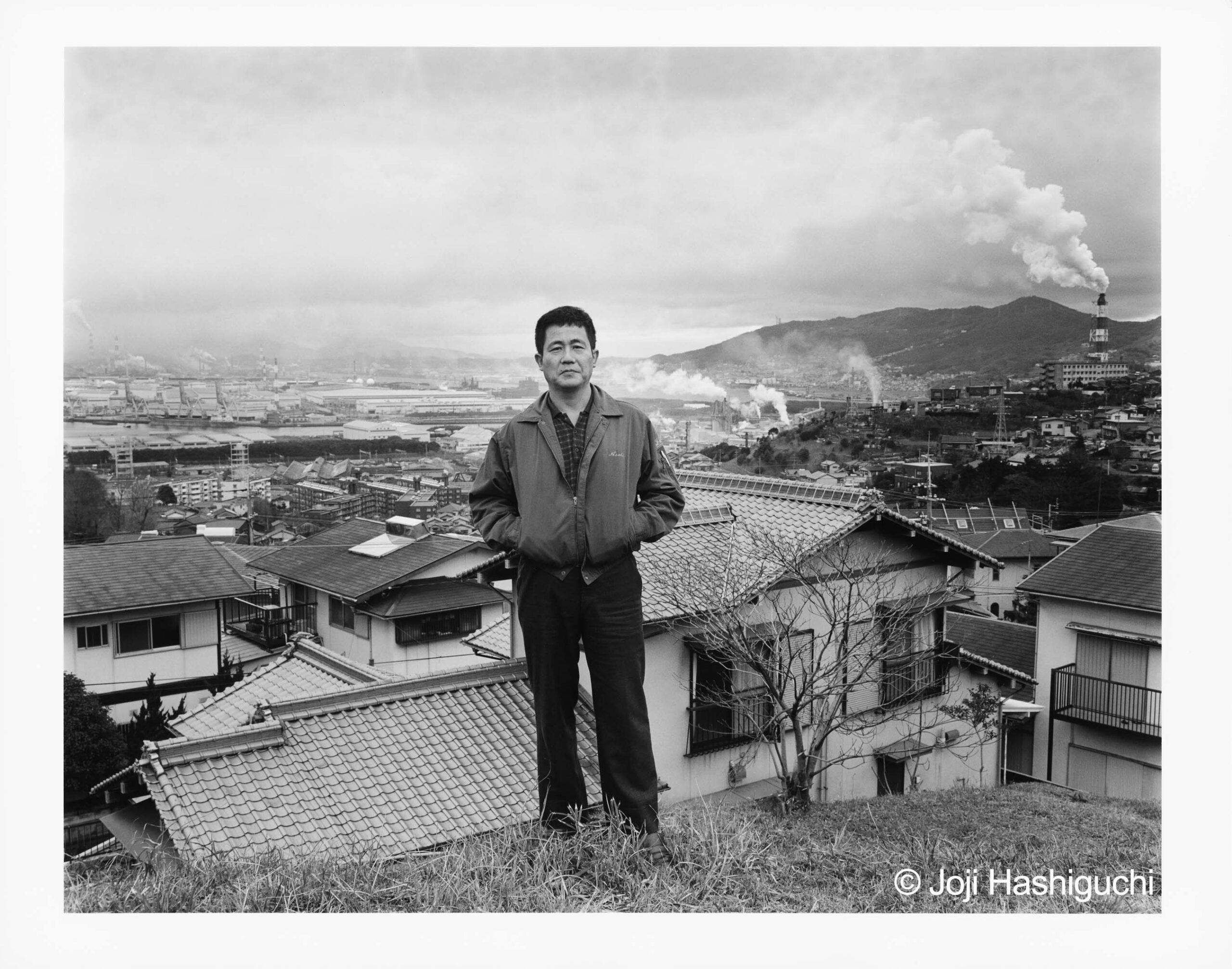

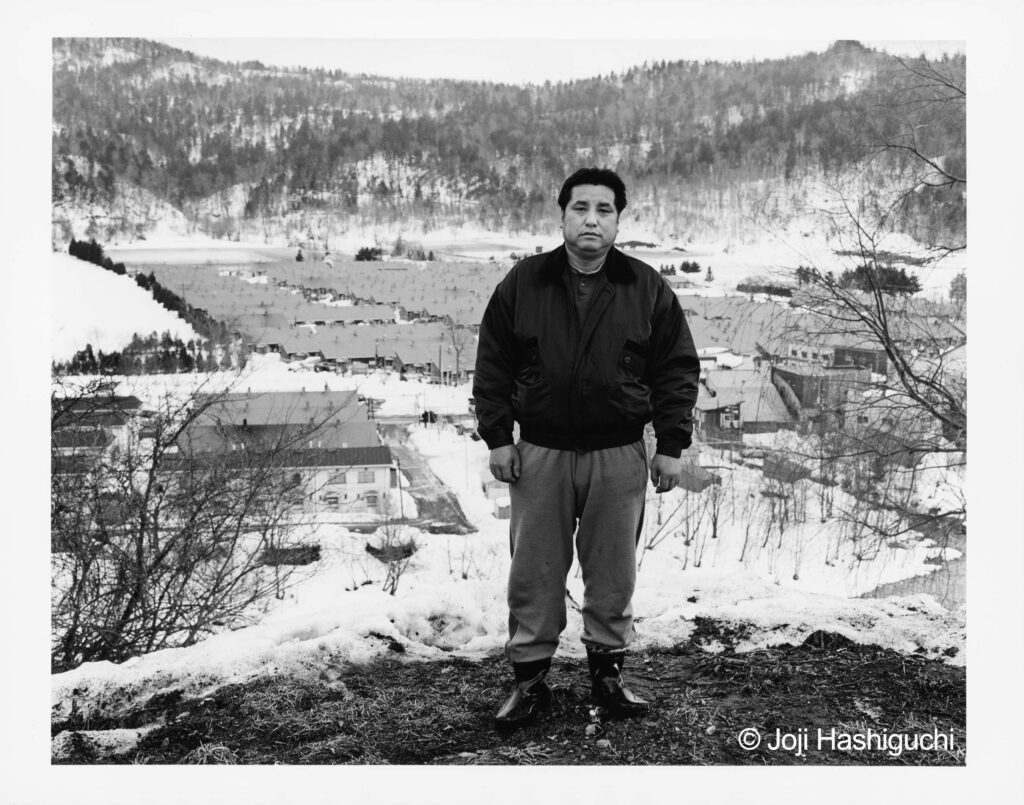

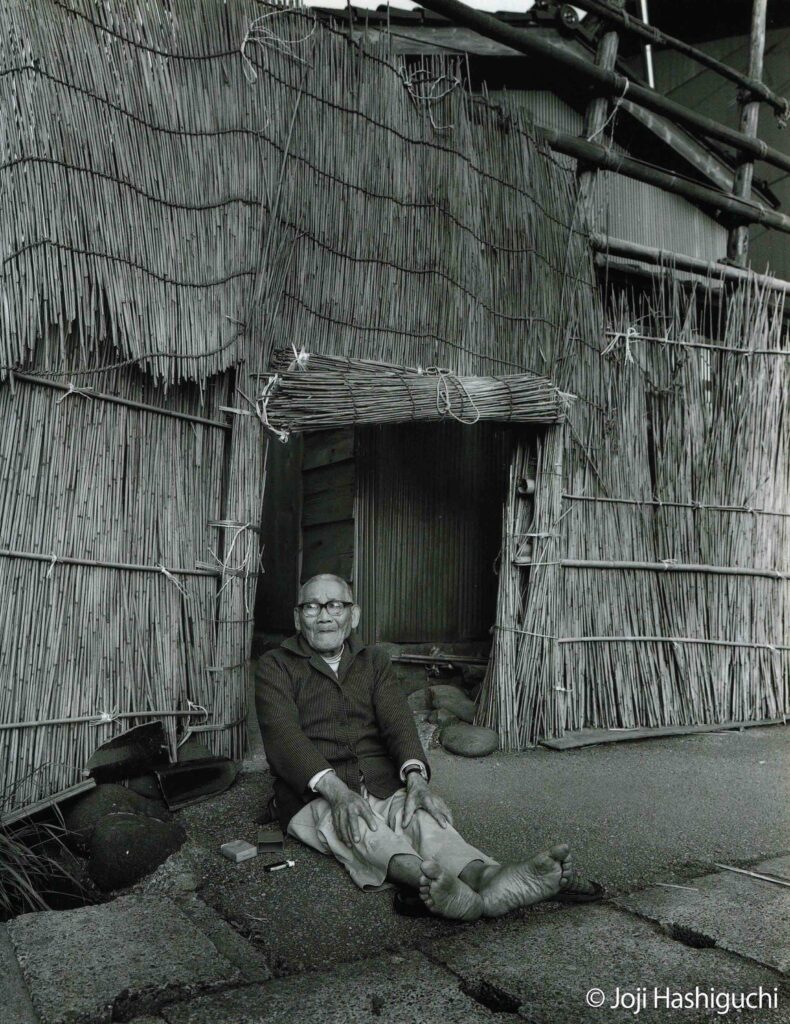

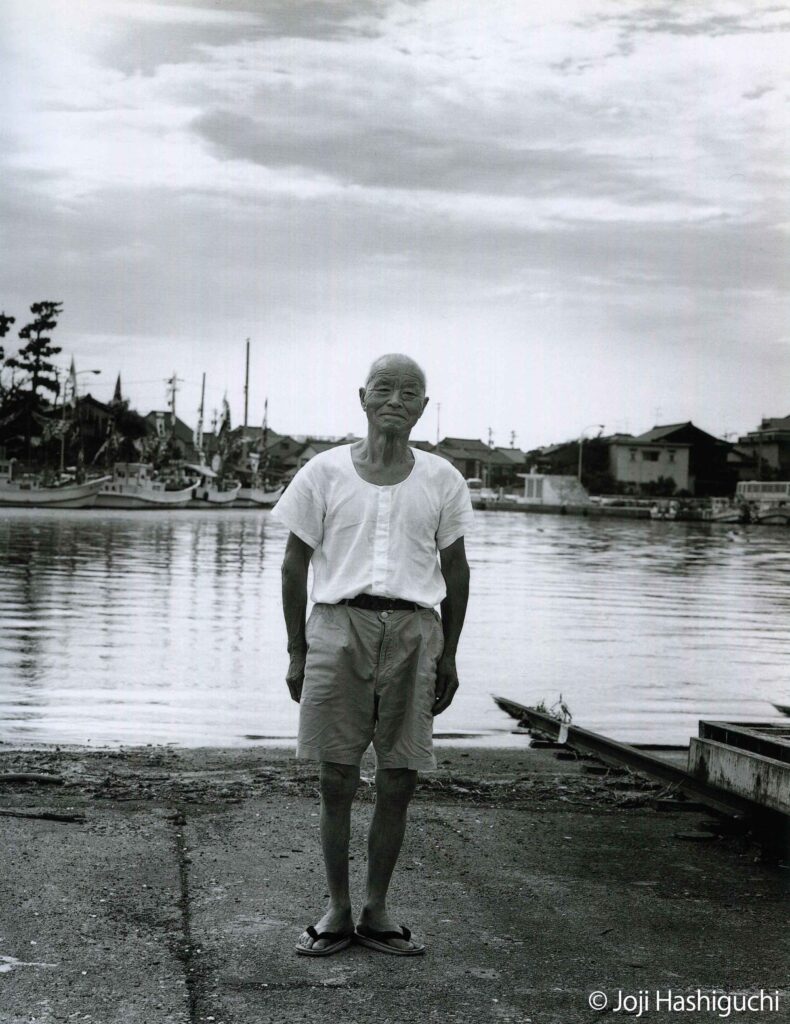

“Father” 1990 (Bungeishunju) : 『Father』1990年 (文藝春秋)

“Father” 2007 (Sangyohenshu-center;New Edition) : 『Father』2007年 (産業編集センター;新装版)

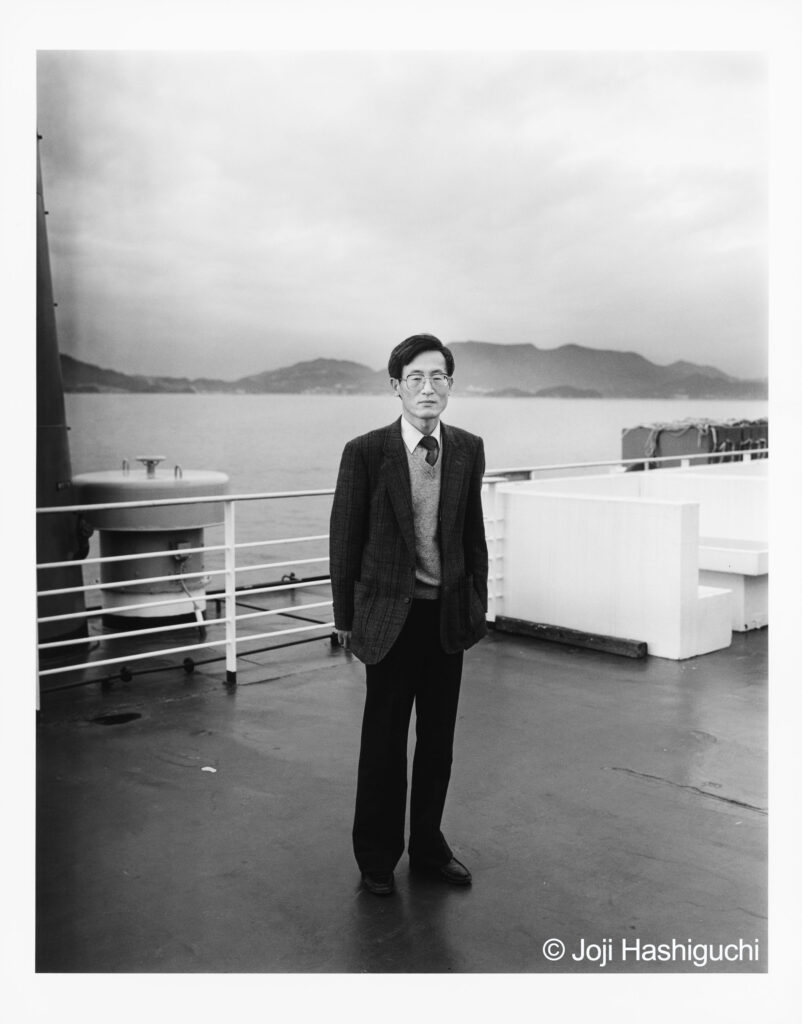

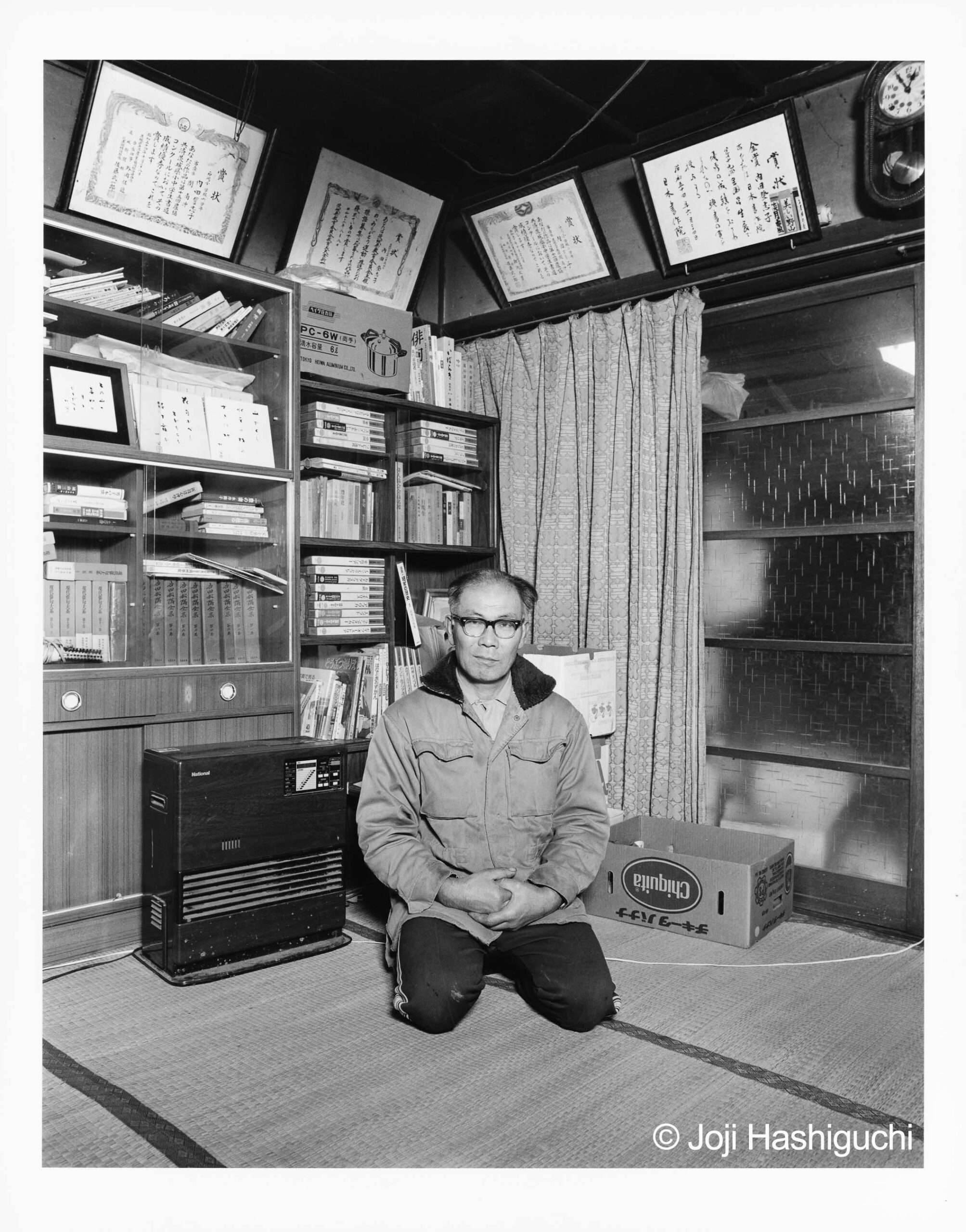

At least since beginning work on “Seventeen” I have come to notice that while mothers in Japan are often talked about by their children, father seem to be spoken of very little. And although Japan continues to be called a “male-centered” society, the males referred to in that expression tend to be the men of organizations and companies, not men as individuals. In addition, while one can see many depictions of ordinary wives in the pages of magazines and in other media, descriptions of fathers are strangely absent.

As a result, while Japan continues to be viewed as a “man’s society”, solitary fathers, or individual men in their working prime, are virtually estranged from social consciousness.

Value judgements aside, within Japan’s current social structure, there exists an image of the father as a dedicated “working warrior”, but it seems rebellion begins before we really get to know the existence of our fathers, and we lose the opportunity of confronting them genuinely as individual human beings. At the same time, I am also impressed with the feeling that fathers themselves do not speak their own minds, but bury their real feelings deep within as the years mount.

And this fact holds true not only with respect to relationships within the family, but with regard to the society as a whole. In that respect, I cannot help thinking that the failure to portray the genuine human image of those people living the most crucial roles within Japan’s social structure is a minus for those of all generations. And it is from these kinds of thoughts that this collection, “Father” began.

In addition to the questions I had previously prepared at the time of my “Seventeen” trip, I also added four new items, inquiring about income, children, pastimes, and their dreams for the future.

これは17歳を訪ねていた時にも感じていたことだが、母親が語られることはあっても、父親が語られることは少ないということを、僕は以前から強く感じていた。そして日本は男性中心の社会と言われ続けているが、そこで語られている男とは、組織や企業であって、個ではない。また、一般の主婦の姿を雑誌や他のメディアを通して知ることはあっても、不思議と父親の姿が語られることはまずない。

このように、日本社会は男社会と位置付けられながらも、一個人の父親、或いは働きざかりの男たちは、ほとんど疎外されたままというのが、現実である。

良し悪しは別にして、今の日本の社会構造の中では、働く戦士としての父親の姿はあっても、きちんとしたお父さんの存在を知らないまま、或いは知る前に反発が始まり、真正面から父と一人の人間として向かい合う機会を逃しているのではないだろうか。それと同時に、父親本人も自分自身を語ることなしに、本心を胸の奥にしまいこんだまま、歳を重ねていっているような気がする。

それは対家族との関係だけではなく、社会全体にも言えることだ。日本社会の基礎的部分を生きる人たちの人間像がきちんと語られないことは、全ての世代にとって僕はマイナスだと常々思っている。そういったいくつかの思いから、この『ファーザー』の作業は始まった。

『十七歳』の時に用意した共通質問の他に、年収、子供に望むこと、リラックスする場所、これからの夢という4つのあらたな質問事項を用意した。

Shooting date: Jun. 1989- Sep.1990, 112 people in total

“Couple” 1992 (Bungeishunju) :『Couple』1992年 (文藝春秋)

“Couple” 2007 (Sangyohenshu-center; New Edition): 『Couple』2007年(産業編集センター;新装版)

“WORK 1991-1995” 1996 (MEDIA FACTORY) : 『職 1991-1995』1996年 (メディアファクトリー)

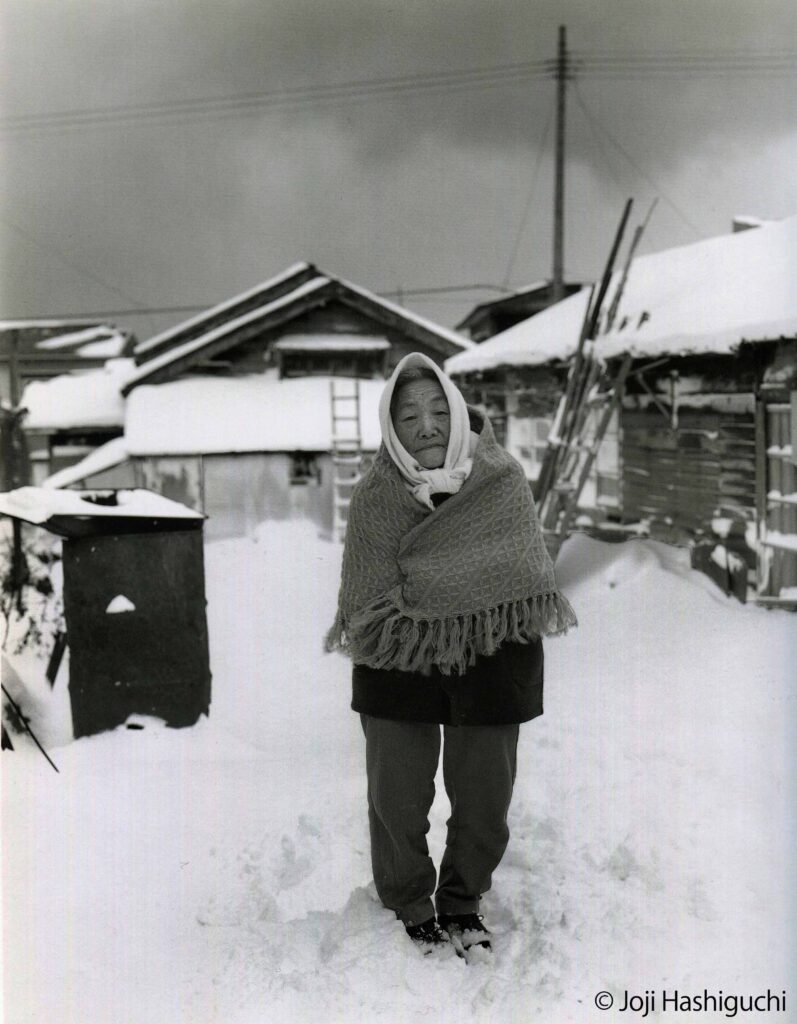

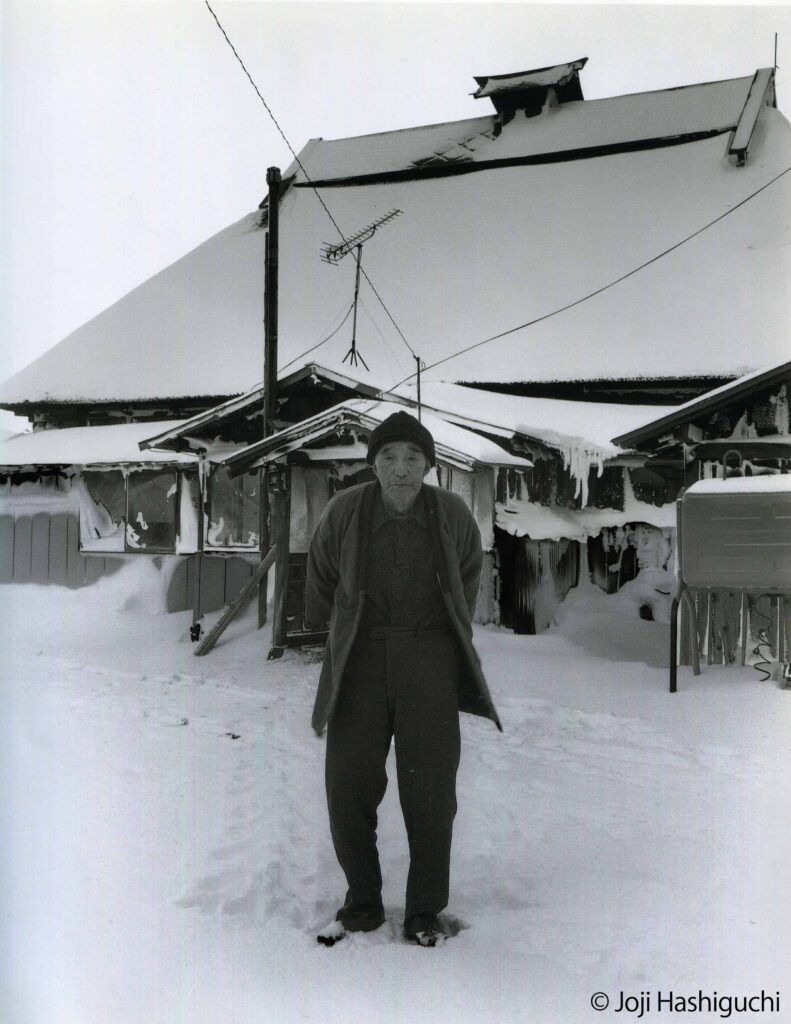

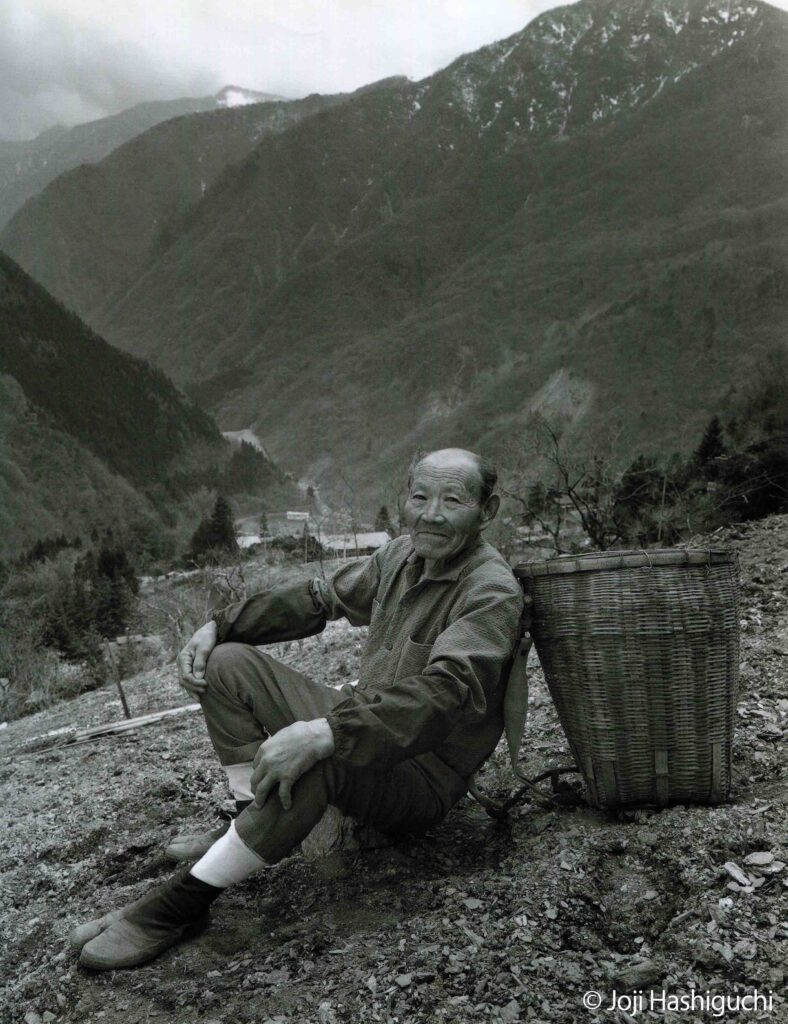

“Dream” 1997 (MEDIA FACTORY) :『夢』1997年 (メディアファクトリー)

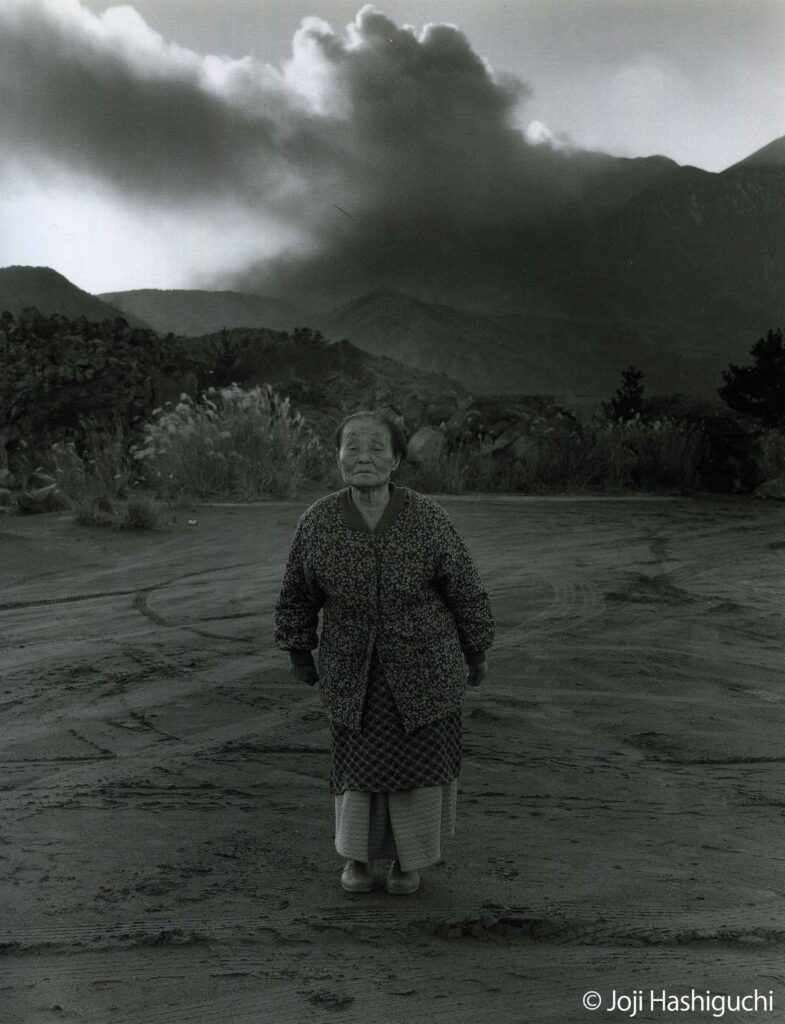

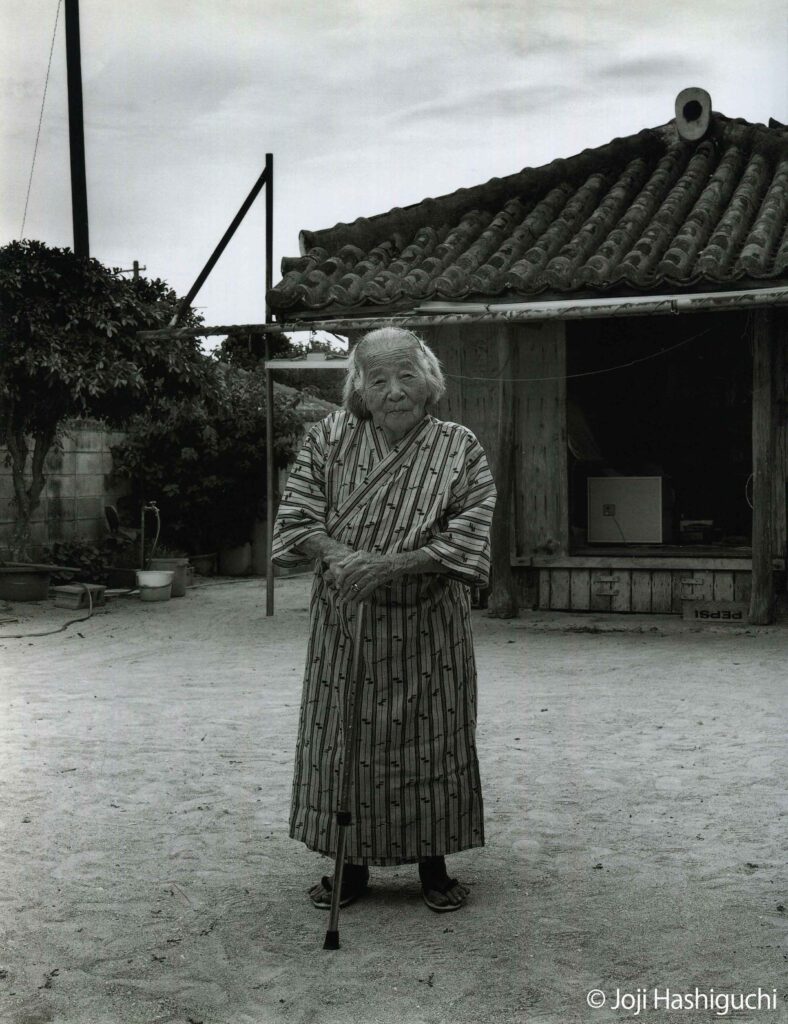

For the work of Dream, I visited people who had lived through the four most recent eras of Japanese history, extending from the Meiji period (1867-1912) through the Taisho (1912-1926), Showa (1926-1989) and into the current Heisei (1989-2019) period; in the same way as for the preceding four volumes, I walked around everywhere, from Hokkaido’s Shakotan Peninsula in the north, to Okinawa’s Yaeyama island and Kuroshima in the south.

Like earlier volumes, Dream is composed of each subject’s responses to a number of set questions, together with the subject’s portrait taken against the backdrop of the scenes and environment in which each person lives. In this volume, however, I added several new questions to my inquiries which I had not included in previous volumes. These questions included, “What places have you lived till now?” “What kinds of work have you done?” And last, “If you could be reborn, what kind of life would you want to live?”

I asked my first two questions since I thought that the personal life and work histories of these people might help me understand the nature of this modern period which Japan has experienced over the last one-hundred years. My final question was based on the hope of understanding how these people had confronted and come to accept their own lives.

『夢』では、明治(1867年〜1912年)、大正(1912年〜1926年)、昭和(1926年〜1989年)、平成(1989年〜2019年)と4つの時代を今日まで生き抜いてきた人々を訪ね、前4作同様に、北は北海道・積丹半島から、南は沖縄・八重山群島、黒島まで隈なく歩き回ってきた。

『夢』は、これまでの作品同様、いくつかの共通質問と、その人の生活の場を背景にしたポートレート写真で構成されているが、今回は更に、前4作にはない新たな質問を用意した。「今まで住んだ場所」「今までどんな仕事をしてきたか」そして最後に、「もし生まれ変われるとしたら、どんな生き方がしたいですか?」。

これまで住んだ場所と今までしてきた仕事、この2つの質問を用意したのは、個人史や個人の仕事を通して、彼らが暮らしてきた日本という国が経てきた100年がどういうものだったのか、日本の近代を確認できると思ったからである。そして最後の質問を用意した理由は、自分自身の生を彼らがどう受け止め、向かい合ってきたかを知ることができるのではないか、と思ったからである。

Shooting date: Dec.1993- Mar.1997, 97 people in total

“Children’s Time” 1999 (Shogakukan) : 『子供たちの時間』1999年 (小学館)

The opportunity which inspired me to publish this collection of photographs was a request for cover shots for a small magazine called “Sukusuku Shogakusei”(Raising Healthy Grade School Students)targeting the mothers of fifth and sixth grade students and published by Bennesse Corporation.

During the two years of serial publication, I got the impression that sixth grade students have something inside them which is significantly different from fifth graders. In other words, I felt the existence of a human individuality as well as a characteristic sense of self in the sixth grade students. I myself, of course, have always believed that the self exists inside the individual since his or her birth without distinction of sex or age, but self can not exist until the human himself is aware of its existence. I felt that the sixth grade students had started to become aware of themselves in that way.

ベネッセコーポレーションという会社が出版している、小学校5、6年生の母親を対象にした「すくすく小学生」という雑誌の表紙写真の依頼が、そもそものきっかけだった。

2年間の連載の中で、5年生と6年生とでは、ただ単に学年や年令・性別の差以上に際立って異なる印象を、僕は持った。言い換えれば、6年生の中に固有の自我をを見ると同時に、「個」としての人間の存在を感じたのである。もちろん、自我そのものは年令・性別に関係なく、生を受けた時から個々の中に存在していると僕は常日頃思っているが、同時に、自我は本人が意識して初めて自我として存在しうるとも言える。そして、6年生の彼らは、その自我の存在に気がつき始めているー。

Shooting date: Jan.1996- Sep.1999, 105 people in total