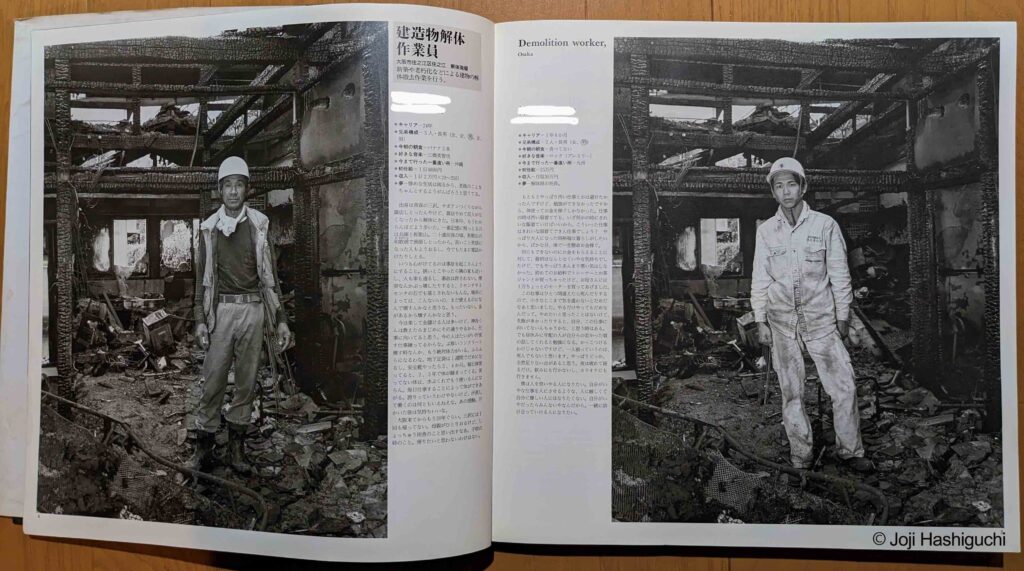

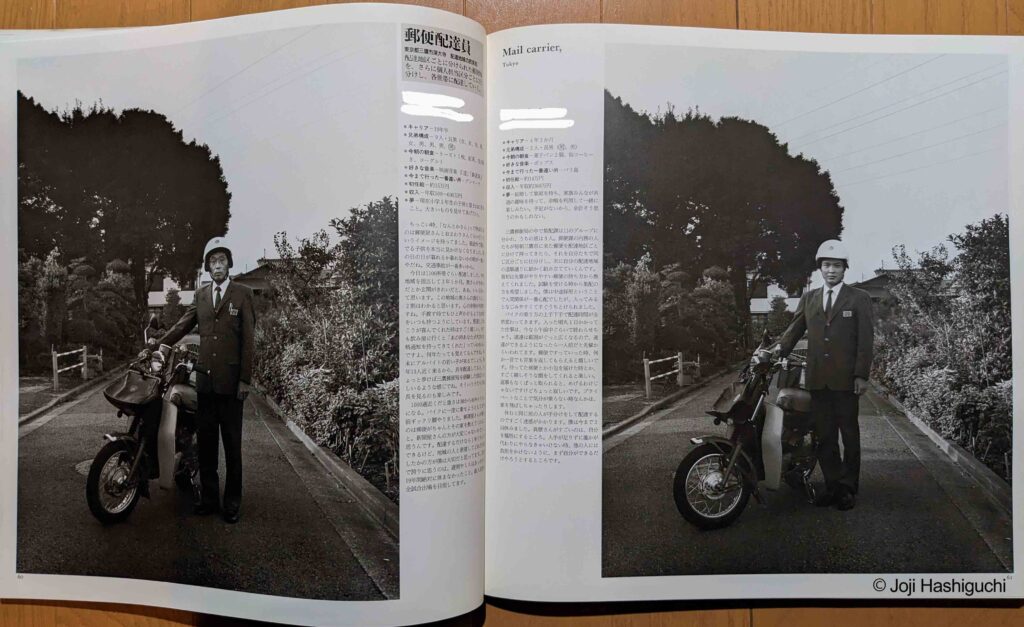

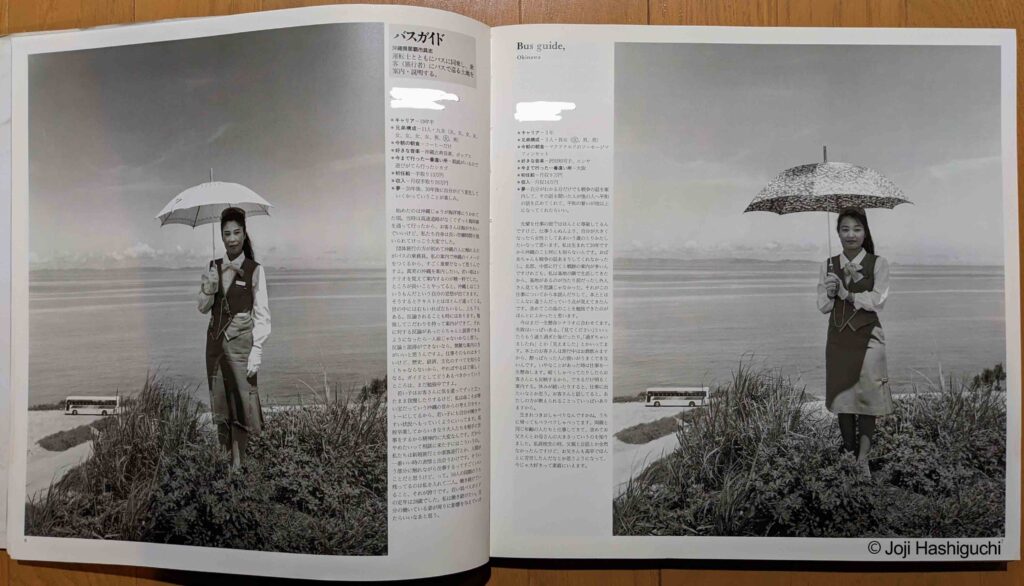

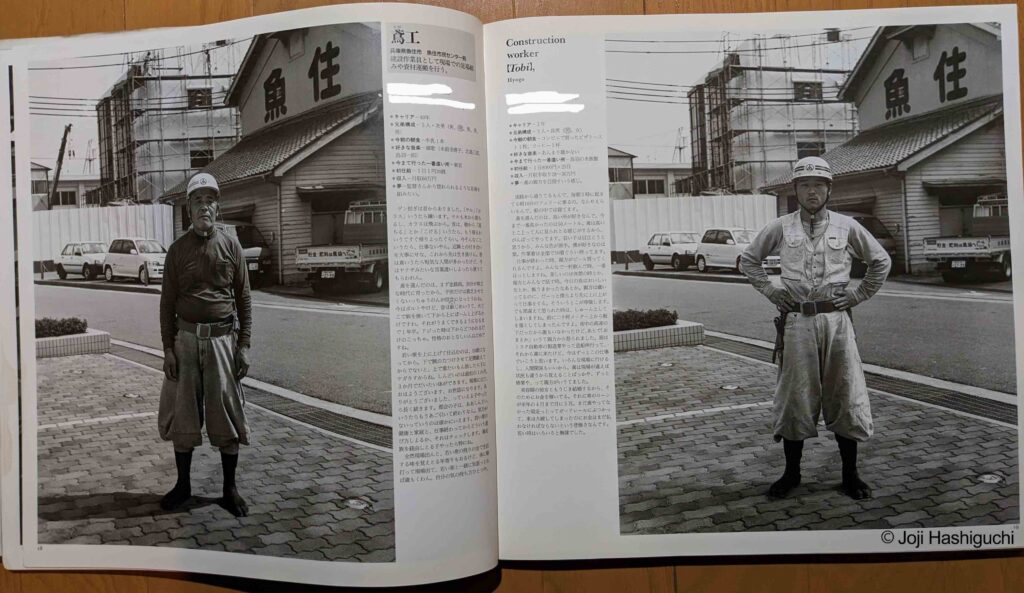

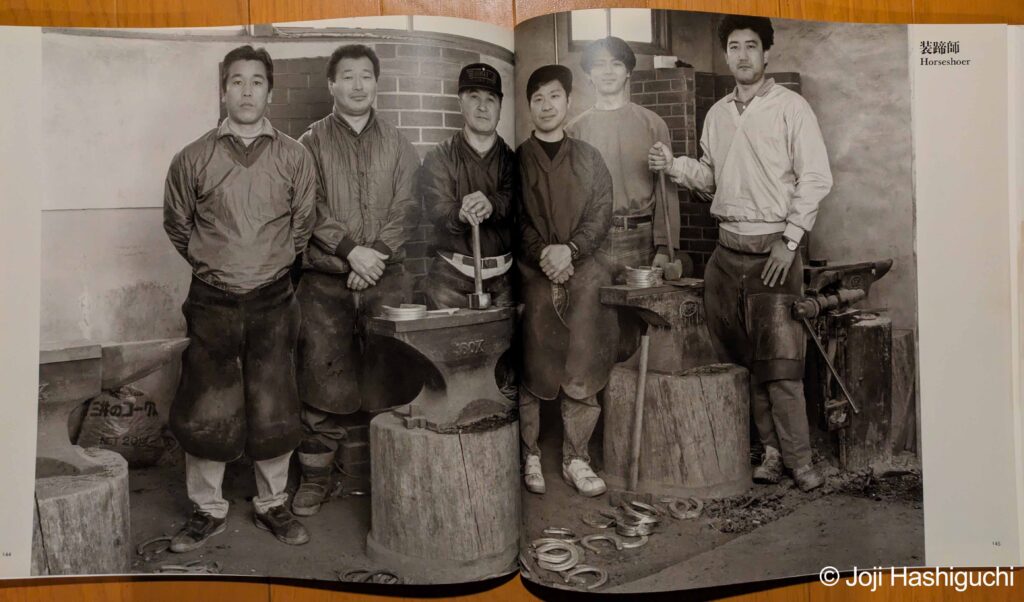

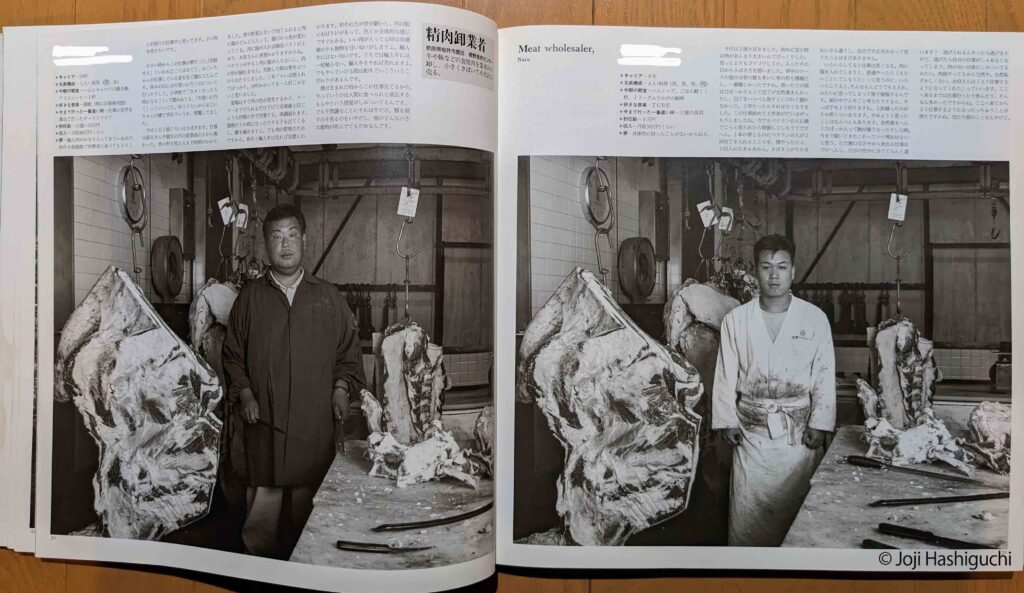

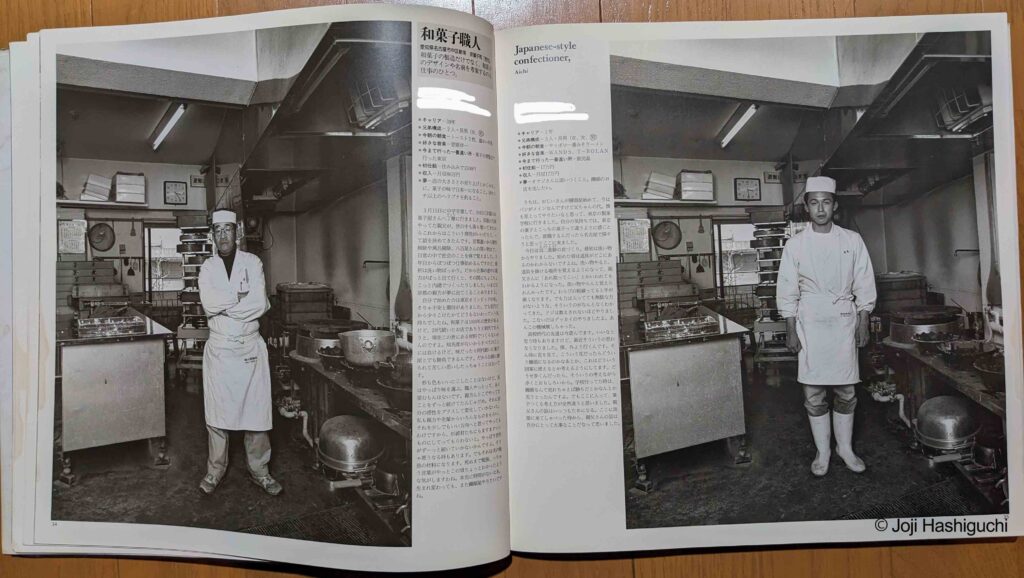

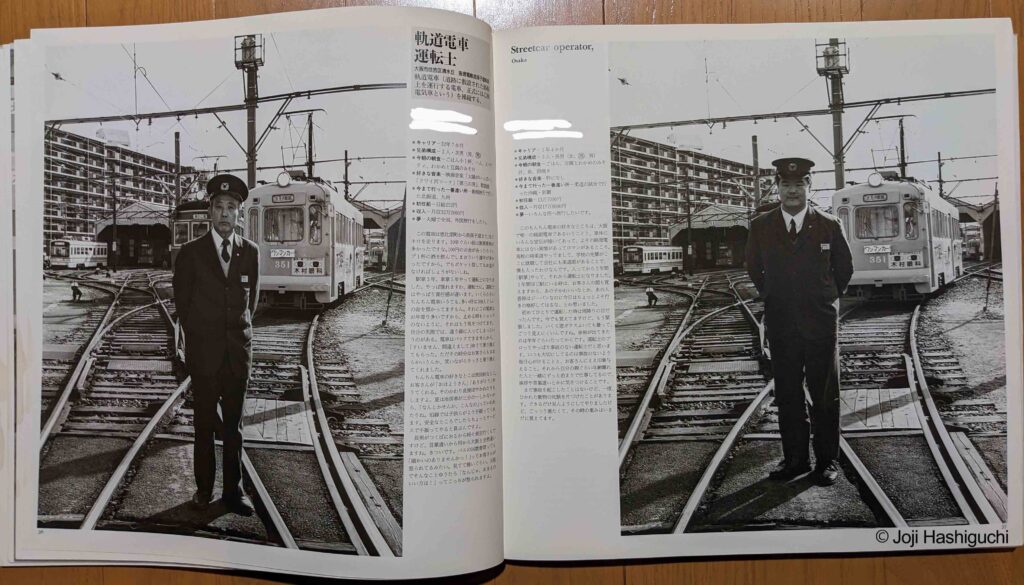

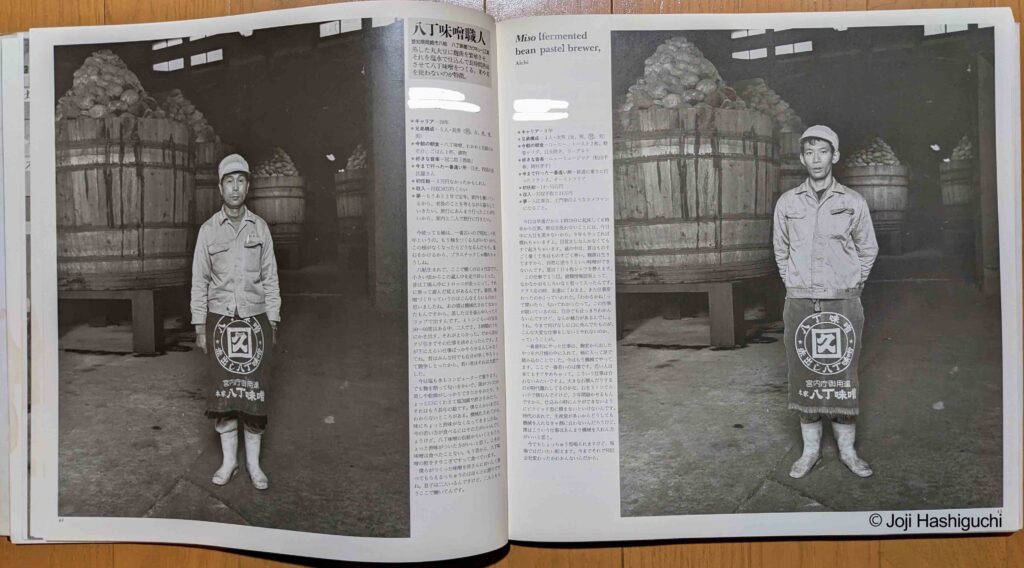

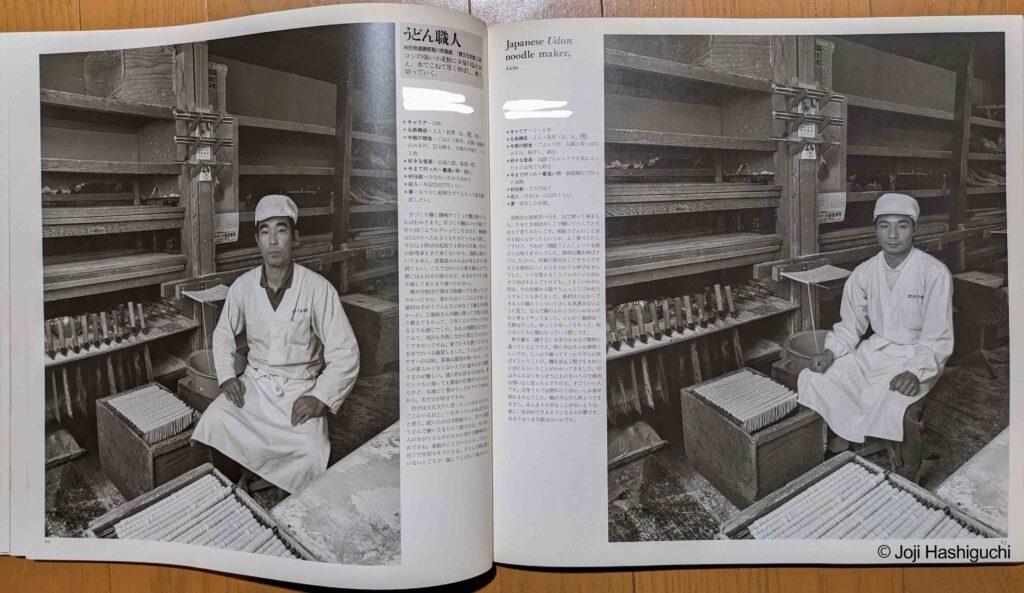

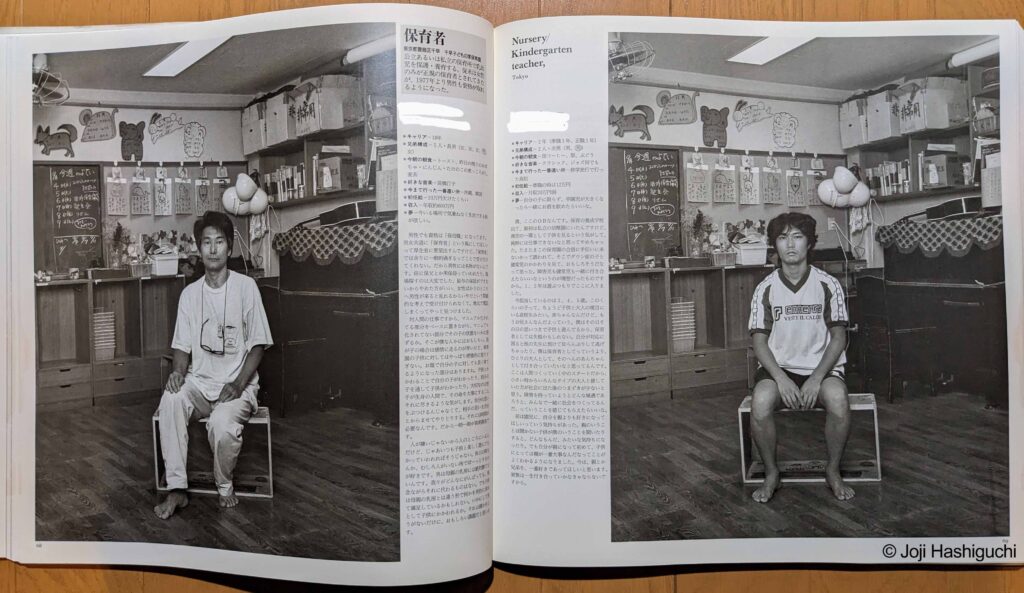

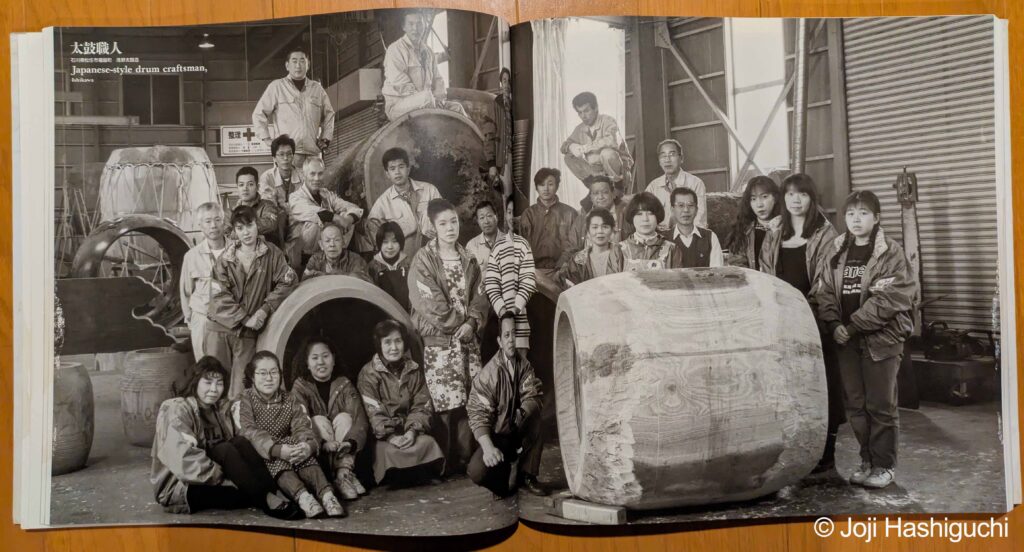

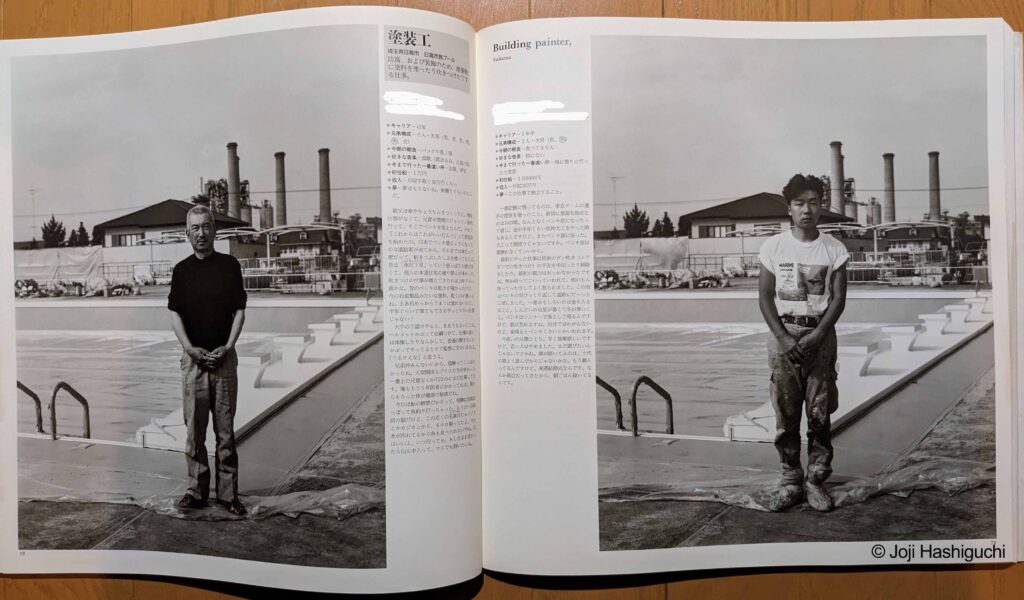

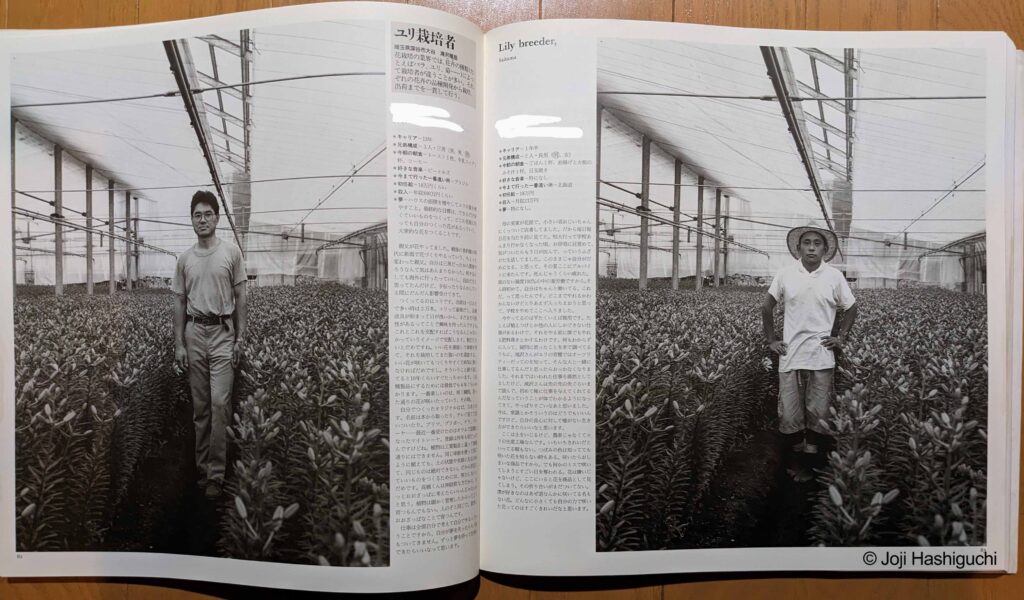

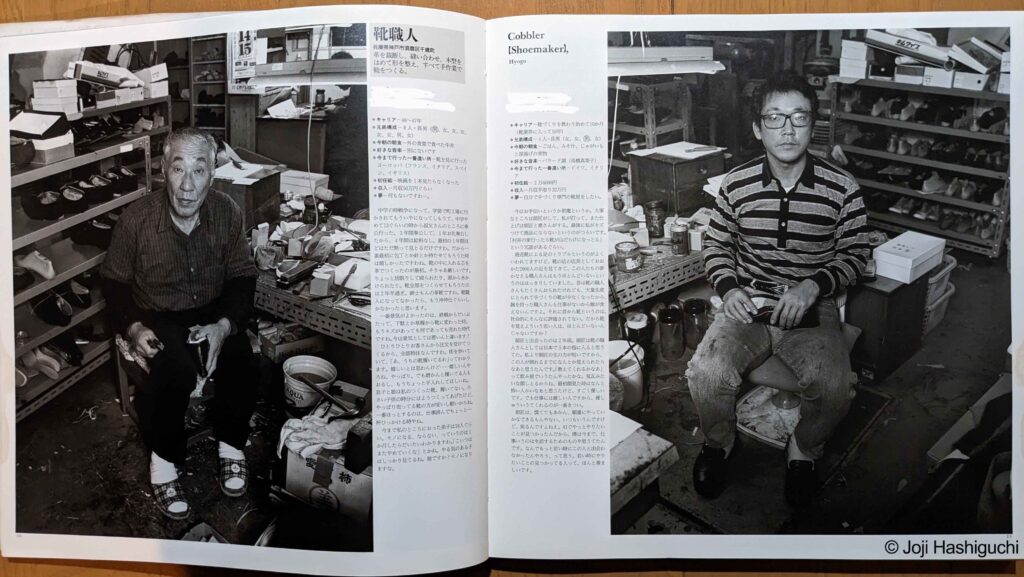

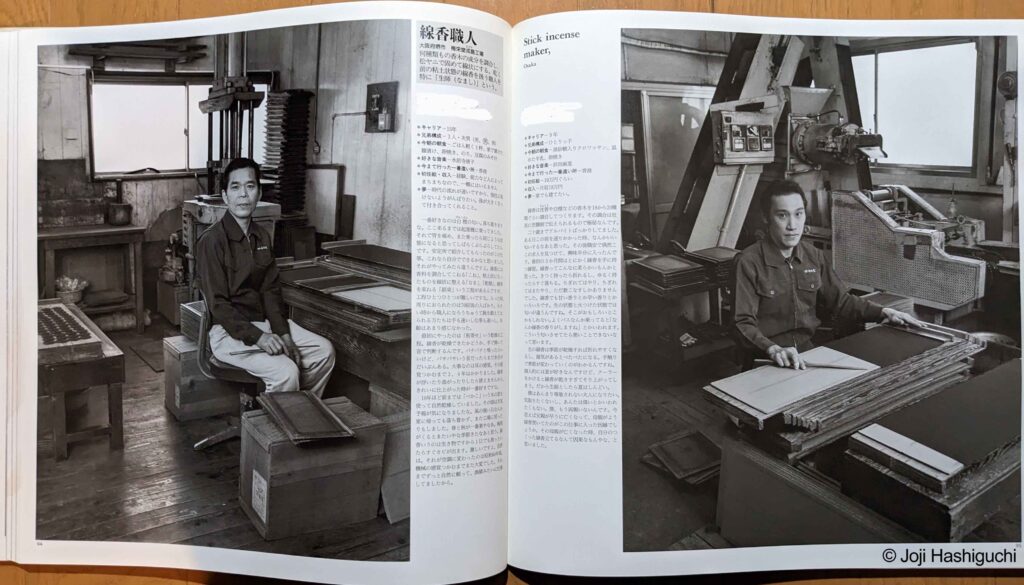

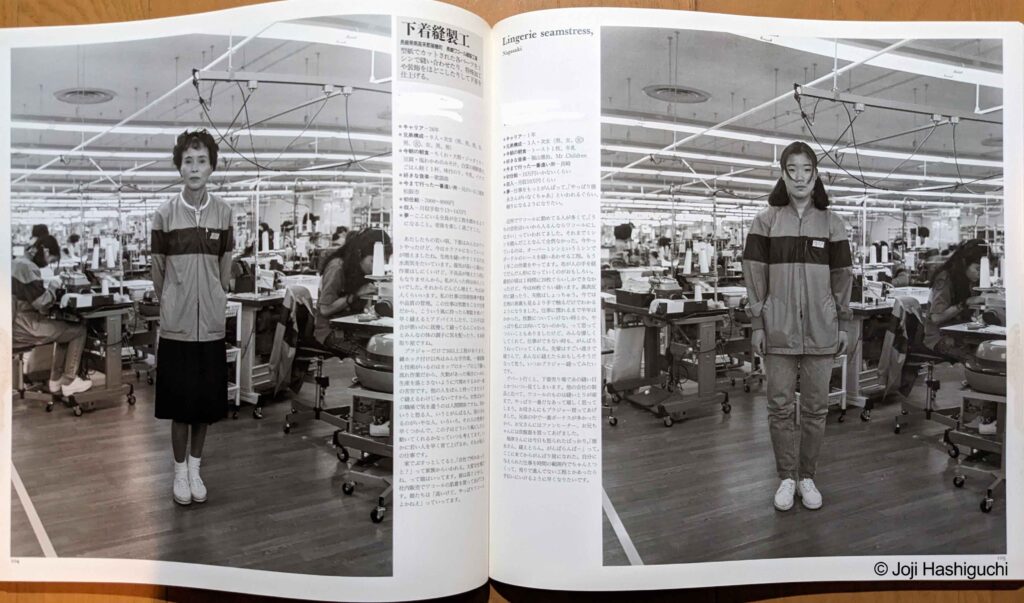

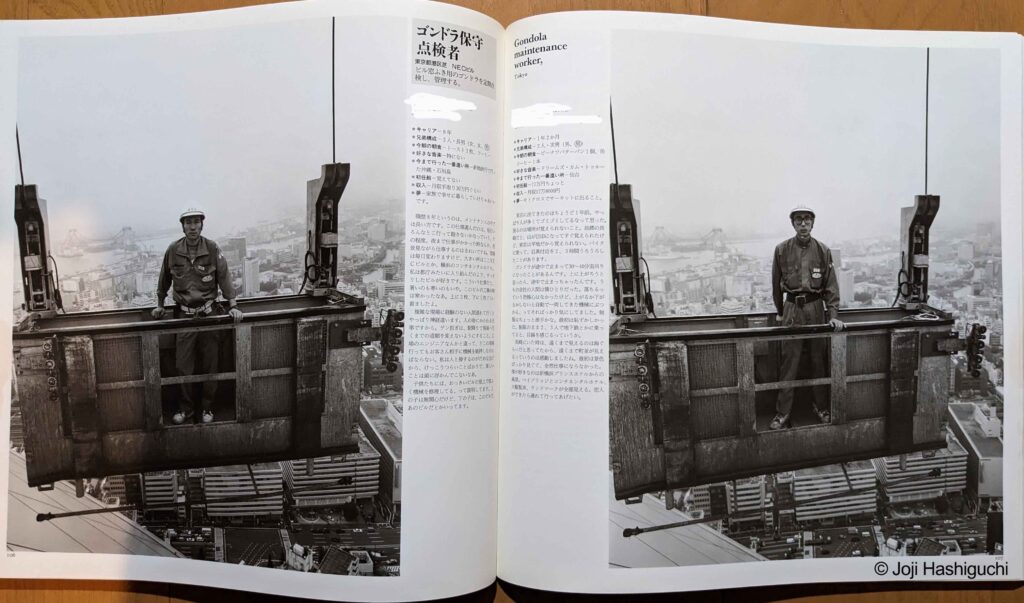

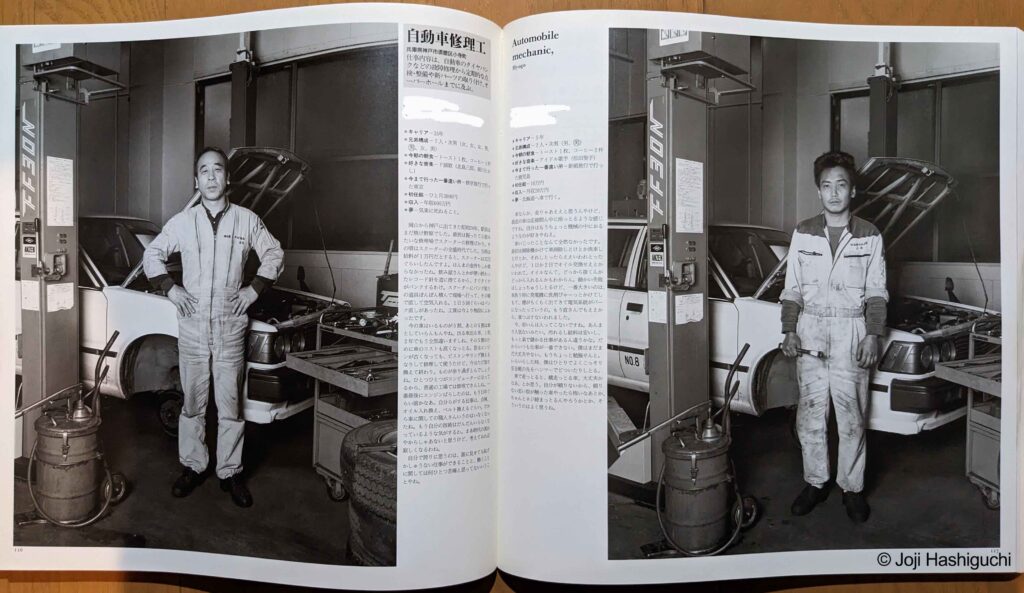

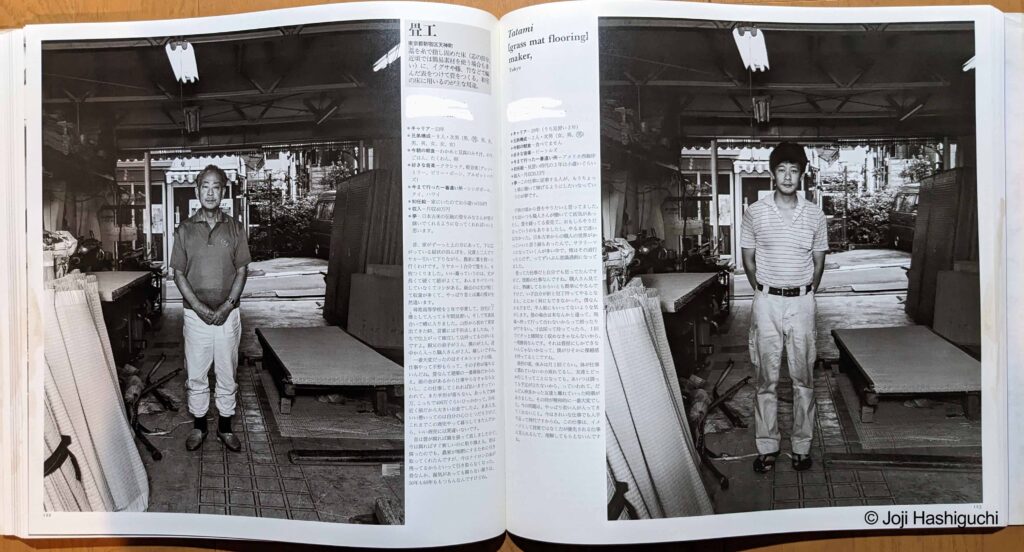

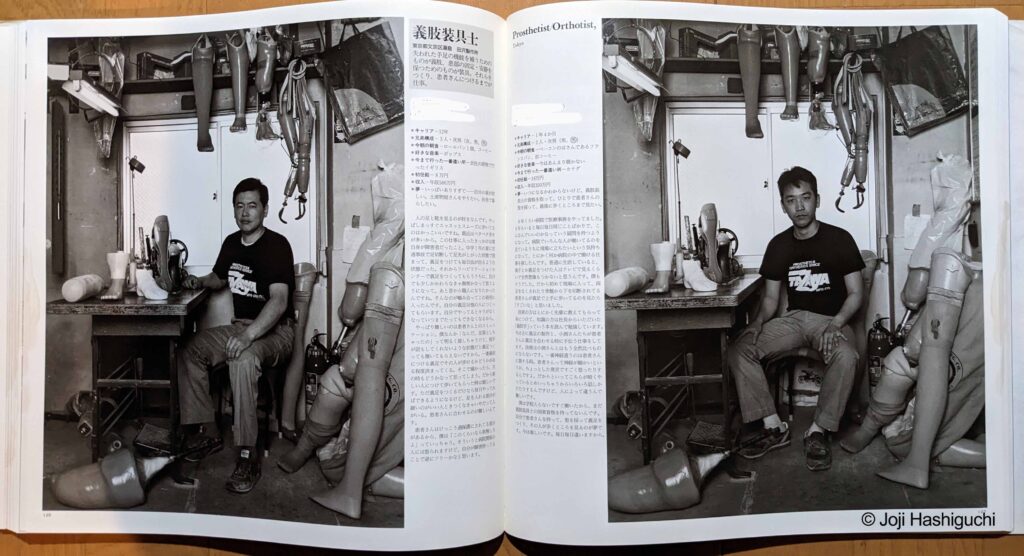

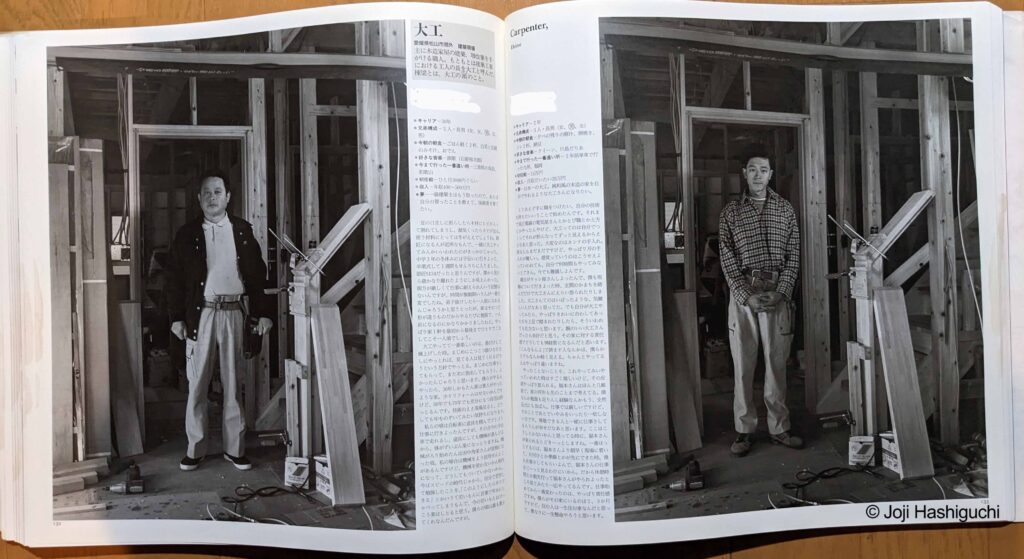

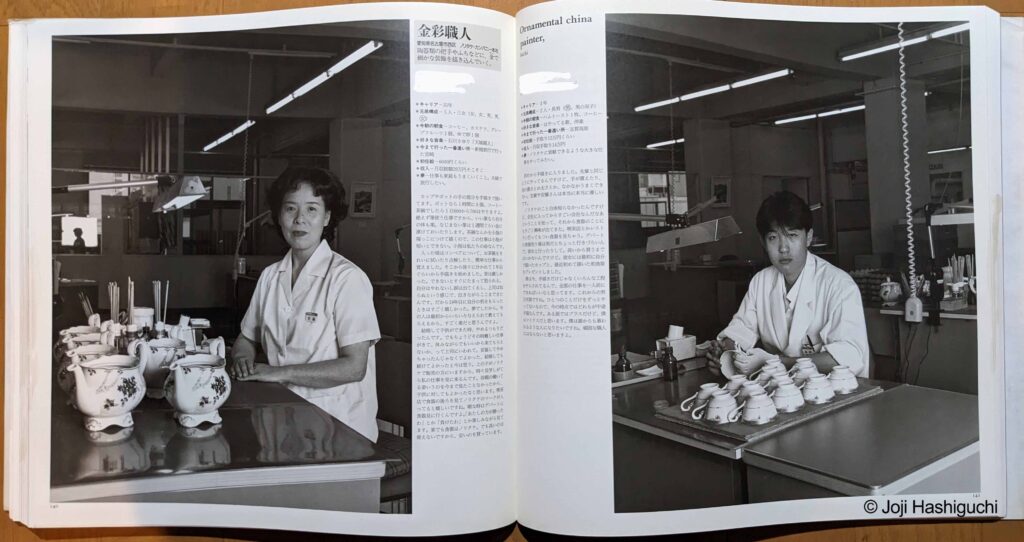

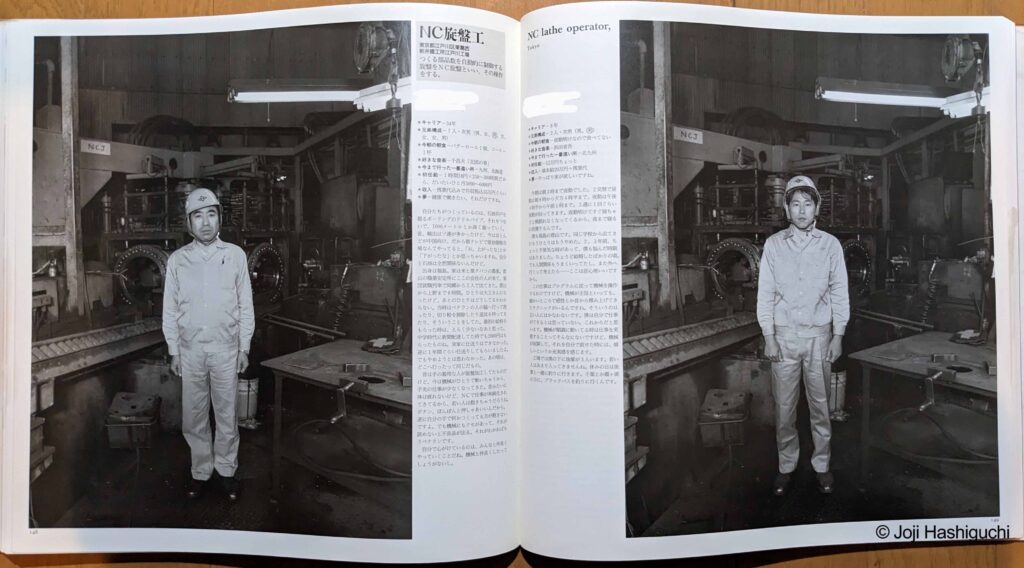

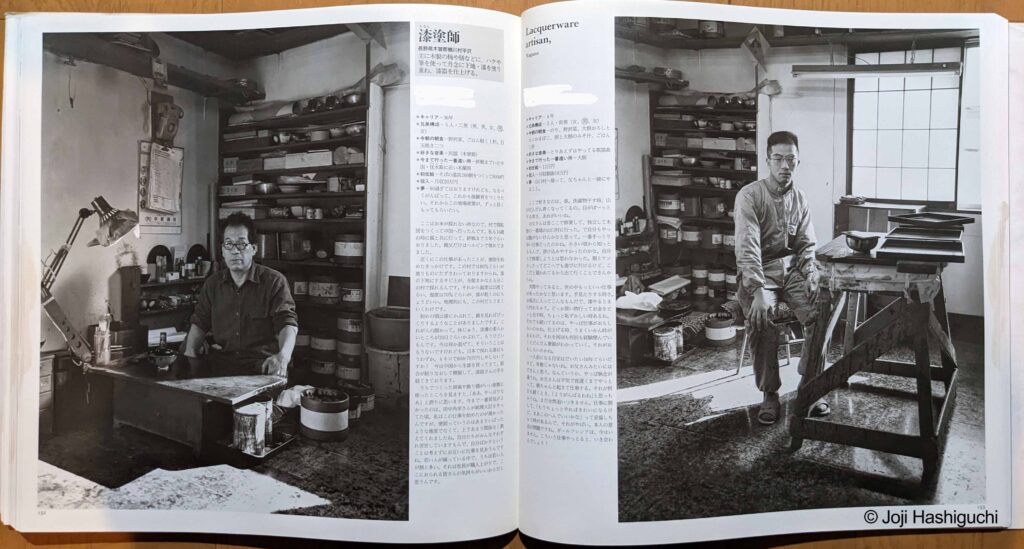

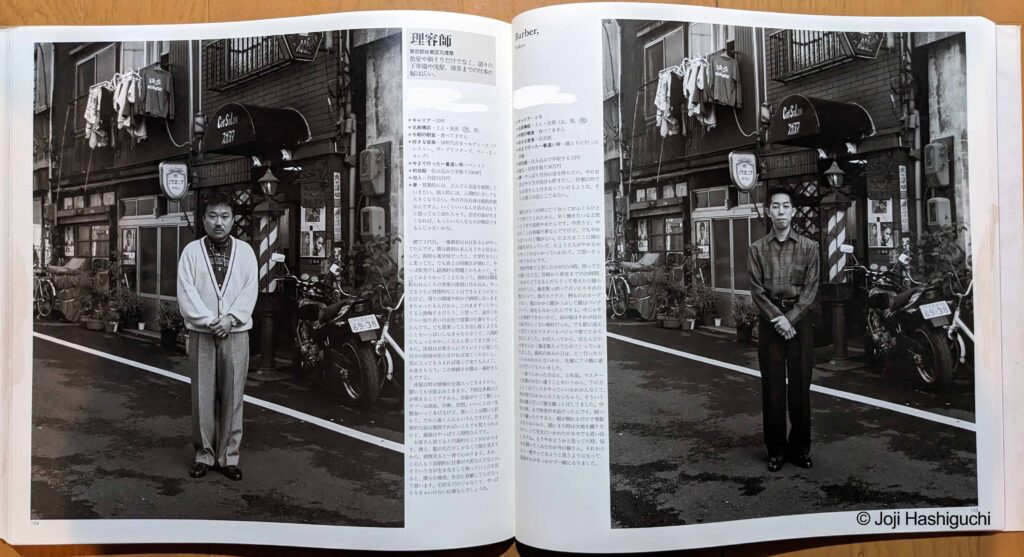

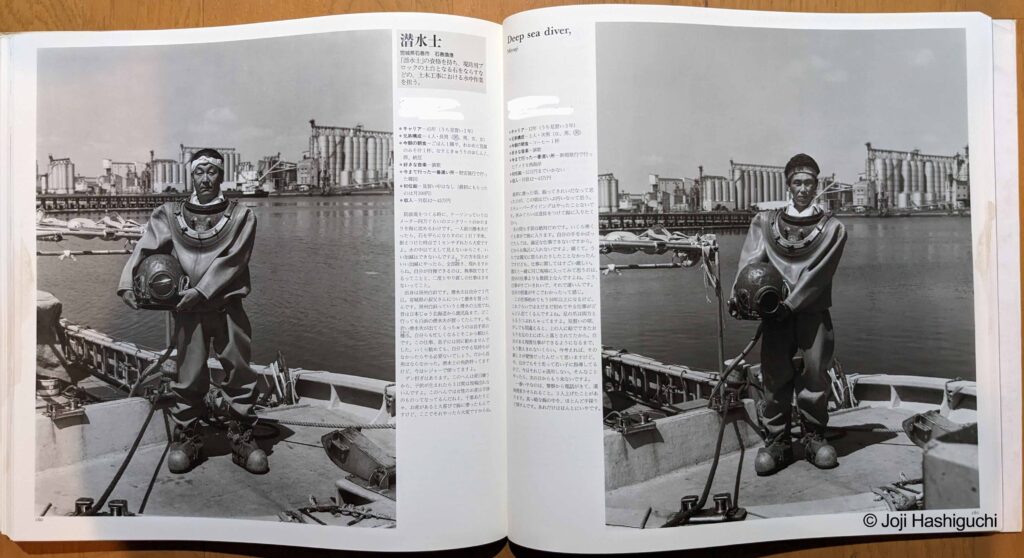

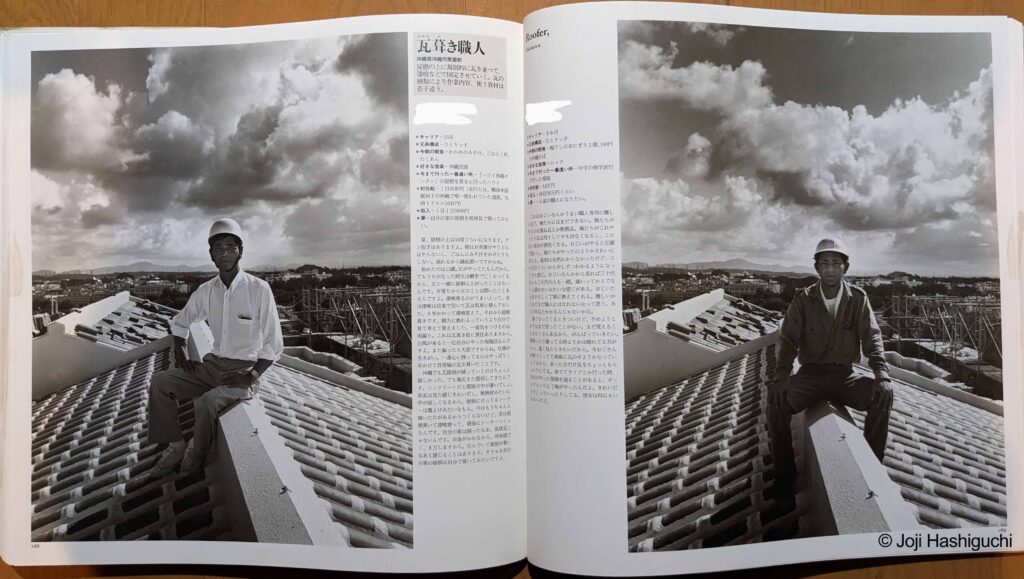

“WORK” is composed of photographs of people taken in the setting of their everyday places of work and presented with several common interview questions. It differs from the previous volumes, however, in the sense that I have used the common setting as a frame to capture on film two people of widely differing agesー one who has worked at the job only one or two years and is just now beginning to understand its appeal, and the other a career veteran who may have worked decades, and who is actively still on the job.

By means of this device, I wanted to learn how persons of differing generations could, by working at the same job, encounter society, archive communication, and build mutual relationality. And I hoped that through the relationship of the individual and his work, I might be able to understand the nature of Japan’s “modern” period, from prewar through the postwar period until now.

この作品「職」はいくつかの共通質問と、その人の生活の場を背景にしたポートレートの写真で構成されている。ただ、これまで発表してきた作品と異なる点は、共通の背景のもとで世代の異なる人間ーまだ仕事を始めて1〜2年で、仕事のおもしろさをわかり始めた頃の若い方と、何十年ものキャリアを持ち、今なお現役で働く先輩の二人を同時にフィルムに収めたことである。

時代背景の異なる人間が、同一の仕事を通じてどう社会と出会い、コミュニケーションを取り、関係性を築き上げてきているのかを僕は知りたいと思った。そして、戦前・戦後からこれまでの日本が歩いてきた近代がどういうものだったのか、個人と仕事のありようを通して見えてくるのではないかと思った。

The Image of the Supporting “Other” ー Yamada Taichi (Scriptwriter, Novelist)

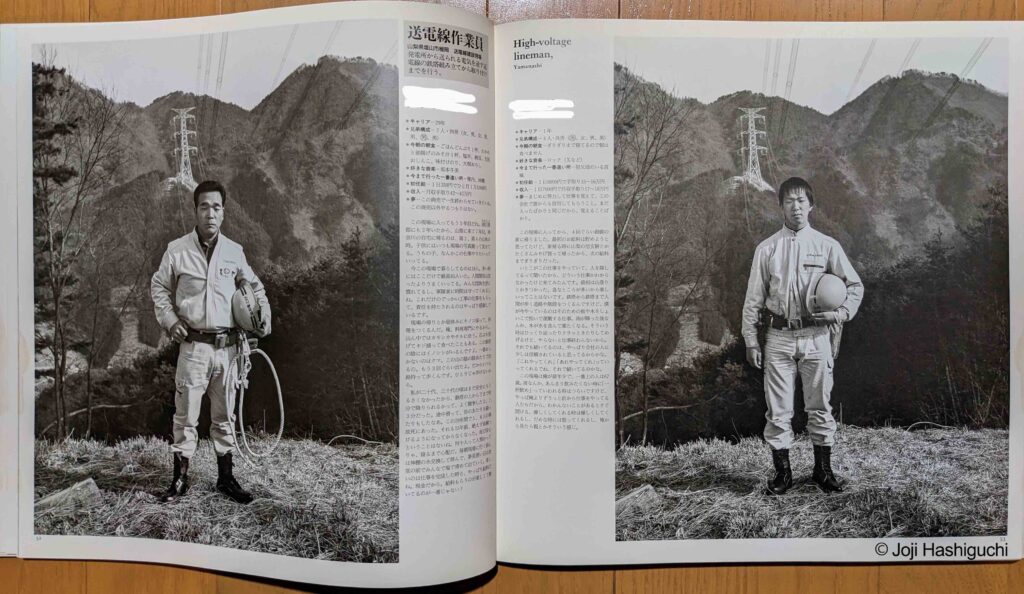

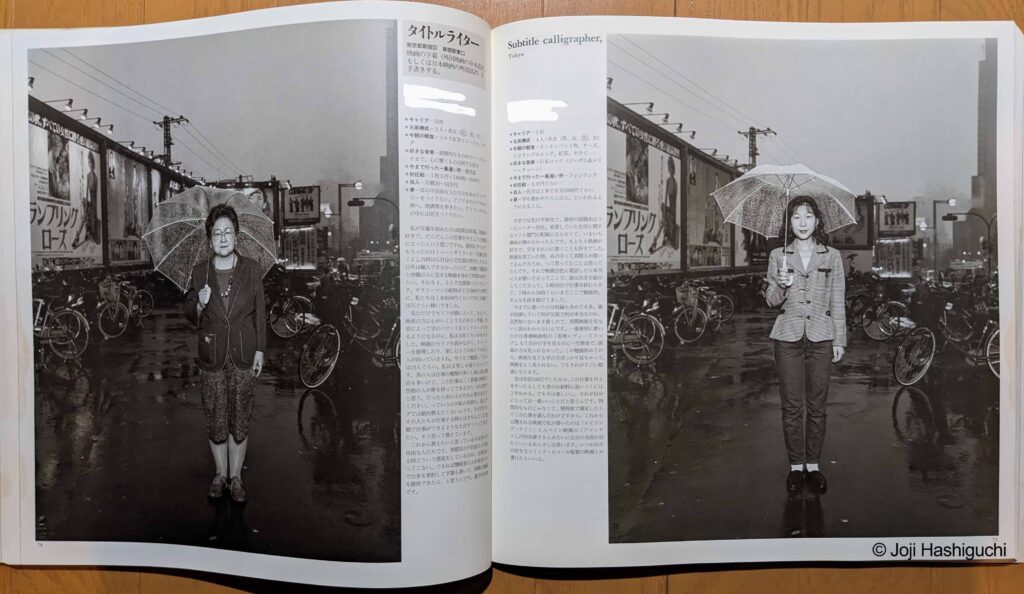

Just as we are sensitive to the fragile luxury of the forest, so we should be more conscious of the fragile luxury of the modern life which we hold in our hands right now. The fact that we return home, flip a switch, and are provided with light is not a natural occurrence. And Hashiguchi has reminded us how it is that such things are possibly by placing these images before our eyes, almost as though saying, “Here, he’s the one who does it.”

When one looks at the images presented so, one realizes to what an extent we fail to direct our gaze at those elements that support and influence the great proportion of our lives, and how much we are ruled by a perspective that pays attention only to what is “amusing.” Moreover, one realizes to what degree that kind of “amusement” has become an inflexible, narrow, restrictive perspective.

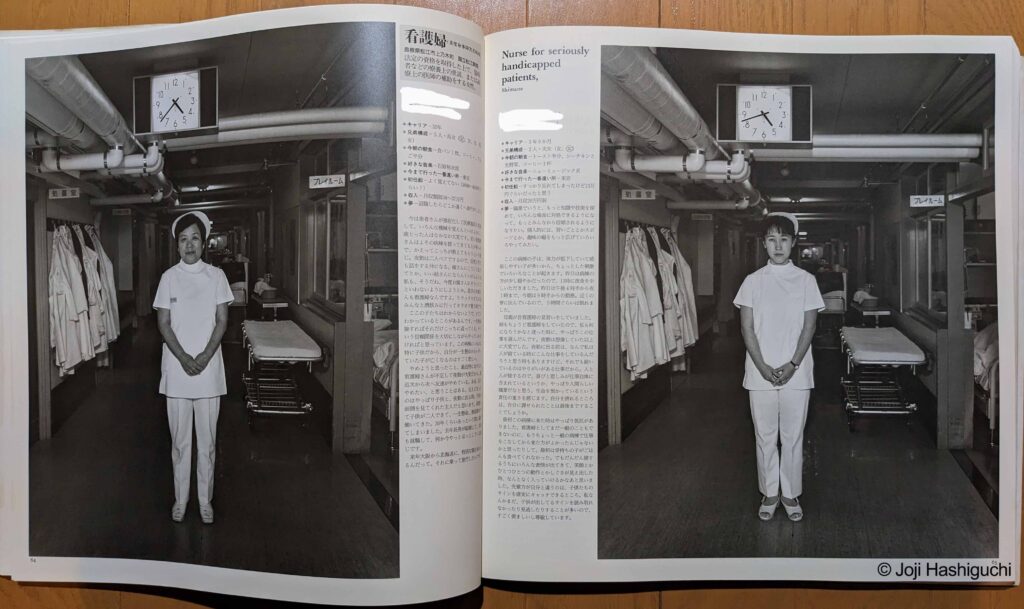

Hashiguchi’s straightforward stance toward his subjects is unique, and unrelated to the kind of brusqueness that would claim to depict reality by approaching the subject so closely as to expose the details of the skin. His work also displays no hint of taunting. He places distance between himself and his subject, but not a criticizing kind of distance. Nor is it sentimentality. But then again, neither is it cold. At times, one feels a sense of esteem for the subject. One might almost call that kind of vision anachronistic, but even so, it marvelously succeeds in fixing a currency that cannot be captured through any other way of seeing.

Likewise, one must not overlook the indispensable nature of the text that accompanies each photograph. Here, too, Hashiguchi has spontaneously escaped the kind of purist orientation that would insist the subject speak only through the photograph. It is the attitude that says, something easily said in words should be left to words to say. The text itself betrays no hint of attempts at self-expression, but is merely the subject’s natural words recorded, as is, during interviews. But what one senses most strongly as these words merge with the photographs is something occasionally so deep and diverse, that it at times brings an unexpected start. Together with the character and flavor wafting from these photographs is the sense of how extremely “adult” the work is.

私たちを支えてくれている他者の姿 ー 山田太一 (脚本家、小説家)

私たちは、森の豊かさ脆さに敏感であるべきなのと同じ程度に、いま手にしている近代の豊かさ脆さに意識的であるべきなのである。家に帰りスイッチを入れると電灯が点くことは、自然なことではない。それを維持しているのは、ほらほらこの人なのだ、と橋口さんは、その姿を目の前にさし出してくれた。

さし出されてみると、私たちの社会が、いかに自分の生活の大半を維持し左右している要素に目を向けていないかに気がつく。いかに「面白づく」の視点に支配されているかに気がつく。しかもその「面白さ」が、いかに硬直して狭く不自由なものになっているかに気がつく。

橋口さんの対象と向き合う姿勢は独特なものだ。それは、対象に近づき、皮膚のディテールまでむき出しにすれば実相が見えるというような客気とは無縁である。揶揄するようなところも少しもない。対象から距離を置くが、批評的ではない。感傷もない。それでいて冷たくない。時には、対象への敬意を感じる。その姿勢は、ほとんど反時代的といってもいいだろうが、そのような目でしか捉えることの出来ない現代が見事に定着されている。

そして、添えられた一枚一枚についての文章も欠かせない。ここでも橋口さんは、写真だけに語らせるというような純粋志向を何気ない姿勢で脱している。文字で簡単に伝わるものは、文字に託せばいいという姿勢である。その文章も、自己表現の気配はまったくなく、聞き書きのメモといった趣である。しかし、写真と共に訴えて来るものは、虚を突かれる思いがするほど時に深く、多様である。写真から匂う風格、味わいと共に、いかにも大人の仕事である。

Shooting date: 1991-1995, 154 people in total