11.6~12.20.2017 at Tokyo Polytechnic University / 2-9-5 Honcho, Nakano-ku, Tokyo 164-8678 Japan

Commentary by Mika Kobayashi, visiting scholar at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

I was in my first year of college when I first saw 17-sai no Chizu(1988)(ⅰ), The 17-year-olds in the photographs were born a few years earlier than me. I remember how I read the book over and over again, comparing my appearance to them, and recalling on my 17-year-old mind. Each of the 17-year-olds had their stories and future dreams printed next to them, and as I read, I felt like their real voices were echoing in my mind, because the quotes and their nervous faces perfectly told how hesitant and reserved they were, almost as though they were making a confession. Turning the pages in the library, I imagined how I would be shot, and what stories I would tell. Come to think of it, this was the work that made me think about the distance between the photographer and the subject when the twi meet and talk.

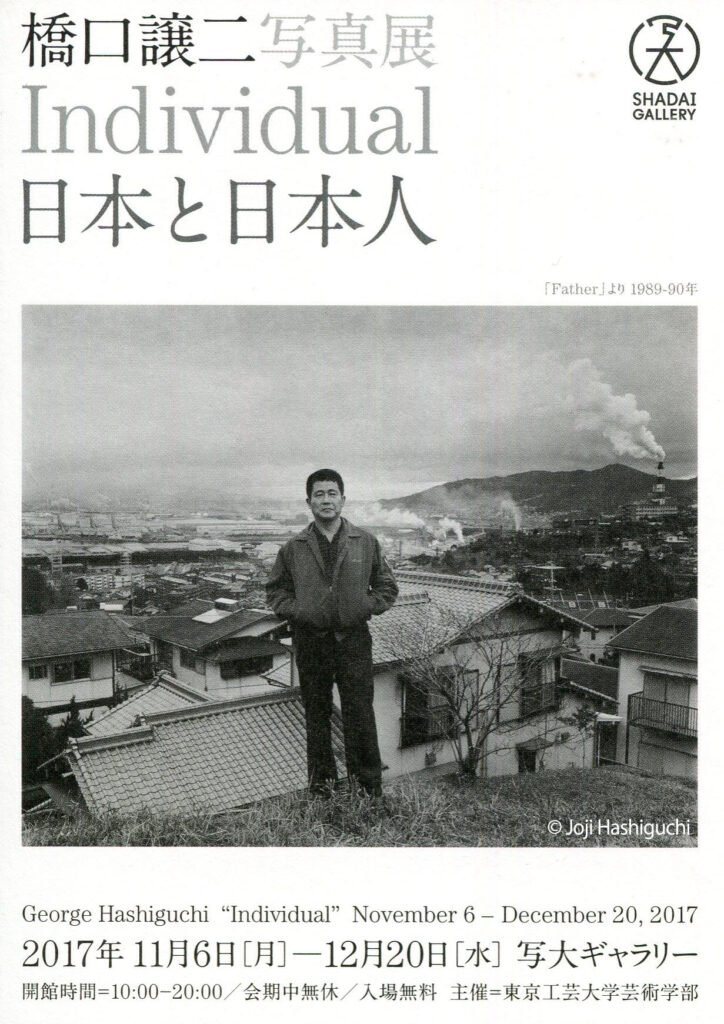

After 17-sai no Chizu, Hashiguchi walked literally all over Japan in pursuit of “discovering Japan and the Japanese people” and published Father, Couple, Shoku 1991-1995 (ⅱ), and Yume (ⅲ) in the following decade. Series after series, his work matures, by portraying the subject in relation to their family role/profession/age and to the environment they live in. Hashiguchi’s attitude to treat the subject as “a person he met at that time, at that place” never changes. This is obvious from the distance he keeps from the subject, and also from the questions that he asks them. The question consistently asked in the series is “today’s breakfast”. “What did you eat this morning?” he asked the subject. This casual question allows us to get a glimpse of the subject’s everyday life. These kinds of questions open up a dialogue, which leads us to a deeper layer of them and closes the distance between the observer and the subject.

It has been 30 years after 17-sai no Chizu was published, and some 20 years after the succeeding series were introduced to the world. When presented this compilation, we can observe the social and cultural features of the 1980s and the 90s in detail. Because these social and cultural features come to the foreground, the categories binding each series-age/profession/social roles -evanesce, and the individuality of the subjects stand out. In other words, the photographs show the uniqueness of each person, by showing them in groups of social categories. In our society, social categories function as a symbol to divide people, to tie them down, and to evaluate them. Hashiguchi utilizes these categories, but at the same time seeks a way to observe each people as a unique individual. What we see when we stand in front of his works, might be the past and present of ourselves.

(Translation by Mizuki Enomoto)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

(ⅰ) 17-sai no Chizu literally translates to “map of a 17-year-old”. All the subjects in this series are aged 17.

(ⅱ) Shoku translates to “profession”. This series features people with various professions at their workplace.

(ⅲ) Yume translates to “dream”. In this series, the artist visits people who experienced the 4 Japanese eras, which are Meiji (1868-1912), Taisho (1912-1926), Showa (1926-1988), and Heisei (1988-present). The eras are determined by the emperor’s accession. The current Heisei era will continue until the descendent of the current emperor, which is expected in 2018 or 2019.

解説:小林美香、東京国立近代美術館 客員研究員

私が『十七歳の地図』に出会ったのは大学に入学した頃だった。写真に写っている「十七歳」たちは私よりも少し年上の世代。彼らの佇まいを十七歳だった少し前の自分に重ね合わせ、写真に添えられた彼らの言葉を自分のことを振り返りながら繰り返し読み込んだことを記憶している。それぞれの境遇、将来に思い描く夢を、躊躇い、言いよどみ、胸の内を告白するような口調をそのままにとどめた言葉は、カメラの前に立ち、幾分緊張した面持ちで視線を向ける表情と相まって、読み手の中に声が響くような瑞々しさに充ちていた。図書館で写真集のページを繰りながら、自分だったらどのように撮られ、何を語っただろうと想いを巡らせた。この作品との出会いは、人と人が出会い、言葉を交わし、写真に撮られる時の距離のあり方とはどういうものなのかということを考えるきっかけになったように思う。

『十七歳の地図』に続き、およそ十年間にわたって「日本と日本人を知る」ために日本中を隈なく歩き回って撮影された写真は、『Father』、『Couple』、『職1991-1995 Work』、『夢』とシリーズを追う毎に、被写体になった人たちを、それぞれが担う役割や関係性、積み重ねてきた時間とともに、周辺の環境の中に描き出す厚みを持った作品として醸成されてゆく。その過程において一貫して保たれているのが、誰であっても「その時の、その場所にいる人」としてとらえる姿勢である。このような姿勢は、写真に表されている被写体との距離としてのみならず、それぞれに投げかけられる質問にも反映されている。どのシリーズにも共通している質問項目が「今朝の朝食」である。「今朝は何を食べましたか?」という問いかけに対する返答は、何の気負いも衒いもなく、それぞれの日常生活の一端を示している。このような簡素な問いかけが起点になり、対話の中で紡がれた言葉が、写真に写る人と写真を見る人との距離を縮めるものになっている。

『十七歳の地図』が刊行されてから30年近くが経ち、その後のシリーズが発表されて20年前後が経った今、それぞれのシリーズの中から選び出された作品を通覧すると、写された人たちの個々の存在とともに、1980年代末から90年代までの景色が、時代を物語るさまざまなディテールとともに浮かび上がって見えてくる。景色のありようがより前景化することで、年齢や関係、職業や立場という個々のシリーズを成り立たせている枠組みの輪郭が少し薄れ、写されている人の「個人(individual)」としての存在が浮き上がってくる。つまり、「それ以上分割し得ない(in-divide)」固有性を具えた存在としての人の姿が、十年の歳月をかけ、社会的属性を軸としてシリーズとして複数の編まれた作品から立ち上がってくるのだ。社会的属性は、人を分類し、固定化し、評価を下す記号、カテゴリーとして機能する。橋口は、それらの属性のありように依拠しつつも、人の存在をあくまでも、それぞれに異なる「個人」として捉えることを追求してきた。その証として作品に対峙することは、私たち自身の過去と今を見つめ直すことにつながるのではないだろうか。